July 15th, 2013 §

On Saturday it was time to cull the deformed chick and move Oregano back in with the main flock. Two odious tasks I’d been dreading.

Before removing the two broody hens to their nursery coops, I had finally achieved a nice, stable and harmonious flock. The rooster was sweetly keeping order, and every bird was finally in good health, all wounds were healed and parasites eradicated. Things were going along well. However, whenever a chicken is added or subtracted from a flock, a power vacuum opens and each bird scrambles to attain the highest possible spot in the pecking order. The birds don’t “remember” a former flock mate, even if she was only out of the coop for a month. To all of them Oregano is a stranger, and their instinct is to kill her in order to preserve their own position in the flock.

So I know all this going in, thus the dread, and I tried a few things to see if I could smooth the transition. I put Oregano in the little run outside of the coop and released Calabrese, the rooster, from inside. I figured if he accepted Oregano back in to the flock he would perhaps help protect her from attack by the other hens, or they would see her as less of a threat if she had her baby-daddy on her side.

But when the two of them got together, this happened:

Then this:

And this:

The birds went at each other in a dazzling display of spread feathers and clashing claws. Oregano puffed herself up as large as possible as she fended off Calabrese. Between attacks Calabrese “danced” for Oregano, so he was definitely conflicted about whether to fight or flirt with this “new” bird, with whom he had one biological offspring growing up in a nearby coop.

After things settled a bit I let the other hens out, one by one. Most hens ignored Oregano, and so I thought I was in the clear. So I released them all into the yard, hoping that some free ranging would give them something to occupy their thoughts and diffuse any potential conflicts. The flock ran out, and Oregano ran into the coop. She seemed grateful to be home again and started eating right away. Things seemed to be going okay.

Then I went out in the evening and found the flock, minus Oregano, hanging out at the compost pile in the woods. Oregano was huddled under the fig by the garage, hiding. She had been shunned, and had to take shelter.

I called all the chickens back to the run behind the coop to force them to be together in a slightly smaller space. The hens took turns jabbing at Oregano’s head and she ran amongst them, head down and feathers fully puffed, looking like a football player lumbering down the field. It’s wasn’t peaceful but she seemed to be holding her own. And this was really her own battle to fight. There’s nothing I could do as they jousted.

Oregano spent the night sleeping in a nesting box—a good defensive position—with the other birds on the roosts. Sunday morning all seemed okay, but I had to go out of town for the day and was very nervous to leave the unstable flock cooped up all day. With no where to run, the confined area can be fatal (see Cora’s scalping and near-death experience last summer). But there wasn’t anything I could do as I had promised to go.

Last night I got home around seven and opened the coop immediately after parking the car. As I had feared, I found that Oregano had been attacked.

Her head and comb were torn open and bloody. So the first thing I did, before even letting my poor dog out to pee, was to grab Oregano and bring her inside for first aid. She didn’t even struggle.

Oregano got a Bactine cleansing, then a nice coat of Neosporin. I covered that with a thick layer of black salve, which supposedly tastes bad to attacking chickens. Over all that I sprayed Blu-Kote, a wound dressing. It masks the red blood color that encourages chickens to continue pecking. By the time she was done she looked a fright, but hopefully it would be enough to get her healed and keep the other birds off of her. The good news is that when I checked on the birds this afternoon Oregano didn’t seem to have suffered further injury, so hopefully her disguise is working.

This poor girl. All she wanted to do was have a family. And after a month of sacrificing her own health, she lost her chick, was turned on by her former flockmates, and suffered injury at their beaks. I wanted to raise chicks with broody hens, because it’s less work for me, but I am not sure if the tumultuous flock dynamics makes it worth it. I still have Dahlia to get incorporated back into the flock, and the six babies. Better get a bigger tube of Neosporin…

July 10th, 2013 §

There were no new babies born overnight, but around noon today I found a broken open Coronation Sussex egg. The embryo inside was well developed but still had a lot of yolk, so I know it wasn’t ready to be born. It was the egg that Dahlia chucked out of the nest on the first day of the hatch. Perhaps she did that because the embryo had died, or maybe it was out of the nest long enough to chill and stop developing. We’ll never know.

There was a Black Copper Marans egg in the process of hatching under Dahlia. It seemed to be struggling a bit, but I left it alone. When I came back hours later there was a new chick.

Once the chick had dried, I inspected it. Unfortunately it was born with a severe birth defect. It has only one eye, and its beak is misaligned.

I suspect that there is no sight in its one eye, as it struggles to open that eye and doesn’t seem to respond to any visual stimuli.

I did some quick research and the prognosis isn’t good for a bird born with this defect. Some people can keep them alive with careful attention to making sure the bird gets enough to eat, but most people cull chicks born like this. That is what I plan to do.

The deformed chick, did, however, give me a good opportunity to get all six healthy chicks under Dahlia. I knew going into this that if I had just a few chicks, I would try to combine them under one hen. It didn’t make sense to double the work and cleanup of managing two coops of babies, and I knew that the older the birds got the more trouble I would have when it came time to combine both groups of babies. As I already know how potentially fraught introducing new birds to the main flock is, I wanted to minimize one extra step in the development of a new pecking order.

I chose to take the chicks away from Oregano because of the two birds, she seemed the less serious about mothering. She had pecked at the toes of the Coronation Sussex baby when it was brand-new, and today she was off the nest several times during the day, eating, drinking, and trying to dust bathe in the pine shavings. Not that one can blame her! Perhaps she knew the hatch was done and was trying to get her babies to follow her out to food and drink, but I didn’t get that sense from her.

I was stressed to put Oregano’s three chicks under Dahlia, but I did it one at a time and she didn’t bat an eye. The chicks dove right under her breast like they’d always been there, and there’s been no looking back. In fact, she led her babies off the nest this afternoon, leaving the deformed chick in the nest.

I took the unhatched eggs from Dahlia’s nest and added them to Oregano’s along with the deformed chick. I figured she’d go less crazy if she had a chick under her than if she had nothing and could hear chicks next door. But who knows, maybe she wouldn’t care? Anyway, the plan now is to give any remain eggs another day under Oregano to try to hatch, though I doubt any will, and then return Oregano to the main flock. Which might be tough if they see her as an intruder instead of a flock mate. Geez—managing these birds can really be a pain!

But if I get Oregano back with the flock, I should be in the clear. Dahlia can raise six chicks for as long as she likes, and I will deal with whatever comes next when it arrives. The good news is the six chicks now with Dahlia have spent the afternoon learning to eat and drink.

They are very active in the coop, pecking at everything including their mother’s comb (you can see a little blood spot in the photo above), wattles and even eyeballs, and seem healthy and happy. They run around, and when they are tired they dive into their mother’s feathers for a nap. Can you spot the stowaway?

June 28th, 2013 §

Today marks the halfway point in the incubation of the chicken eggs. It’s been ten days since I placed them under the hens, and my most respected chicken resource states that eggs incubated under broodies usually hatch in twenty days instead of the 21 days for mechanically incubated eggs. We shall see. As it is things aren’t looking awesome in the brood coops, and my confidence in the viability of these hatches is waning.

One of the eggs in Oregano’s coop was broken when I checked earlier in the week, and then yesterday I found the broken shell of a Coronation Sussex egg—the prettiest one of the bunch. Boo.

I don’t know if they are breaking on their own because they are rotten or if she’s cracking (and possibly eating) them. That nest box didn’t smell horribly of rotten egg, so I suspect the egg was fertile when broken. However, I don’t know how many days it would take under the hen for an infertile egg to spoil. So that’s the situation in Oregano’s coop. She’s been getting off the nest, as evidenced by her “deposits” in the cage, and has lost a lot of weight already. Broody hens generally don’t eat much while sitting, and if they do get off the nest their poo has such a strange and horrible smell that it’s enough to gag you just walking into a room with it. Needless to say I remove it as soon as it’s discovered, to keep flies off it and to get it out of my life and into the compost pile.

Over in Dahlia’s coop, I found a major mess in her nest box. One of the olive egger eggs placed under her was broken, and it had made a horrid fermented/cooked mess in the nest. At least five of the ten remaining eggs were coated in dried egg goo. Not good, for several reasons. The incubating egg is a living vessel, and its shell needs to be clean to allow air to pass in to the developing embryo. To seal the pores of the egg could suffocate the embryo.

I was at a loss as to what do. I know the embryos need air, but I also know that to wash an egg is to remove its “bloom” or protective covering that helps keep bacteria out of the egg. In this case, though, I figured washing was probably the lesser of two evil decisions, so I gently scrubbed the dried egg off the dirty eggs.

Oregano had a few dirty eggs too, so I touched those up as well, trying to just wash the dirtiest areas. Then I cleaned out Dahlia’s stinking messy nest, filling it with clean pine shavings. I made notes in my log of which eggs I washed, which may be telling around hatch day.

Of course I started this project before suiting up with gloves, and the stink that was on those eggs was so strong I couldn’t get it off my fingers all night despite multiple scrubbings and soaking in lemon juice. In all, it was a fittingly disgusting ending to an evening that began by killing a black widow in the crawlspace. Ugh.

Tonight it was time to candle the eggs, which means I shine a light through them to see if they are developing into chicks. I made a candler out of a MagLight flashlight (with fresh batteries) topped by a taped-on piece of cardboard to concentrate the beam and cushion the eggs.

Then after dark I headed out to the garage to candle the eggs. All I needed was my candler, my record log and pencil, and a small dish to hold the eggs as I pulled them from the nest. I waited for the garage door lights to go off and began with Oregano’s eggs.

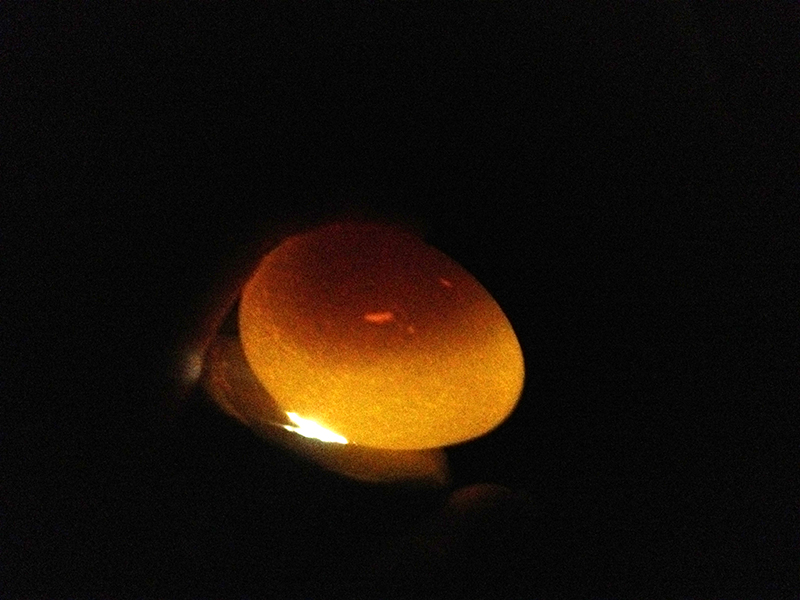

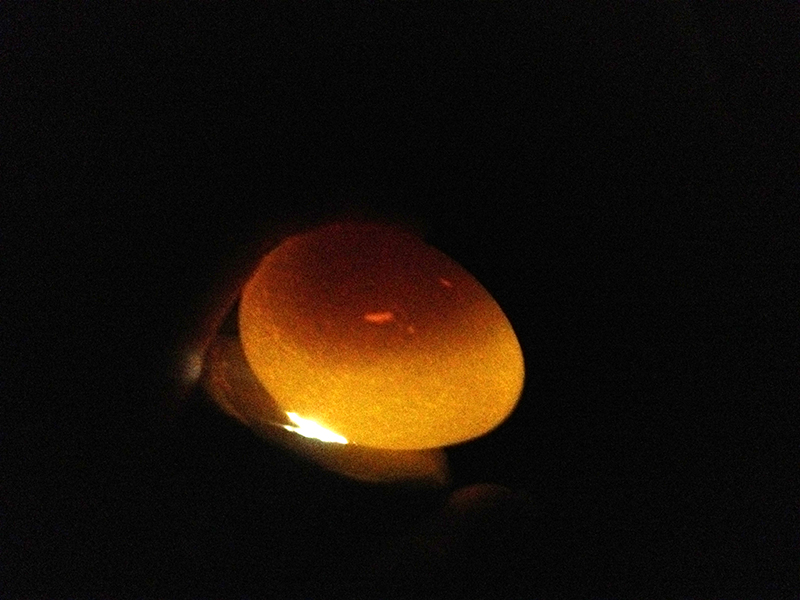

I removed each egg from under Oregano, enduring a peck on the wrist each time, bless her. I held the egg over the end of the candler, turning it until I could see something, or nothing. Most eggs looked like this, below, with some murky shape with no clearly defined blood vessels but perhaps the hint of a developing eye. Perhaps because many of them are Black Copper Marans eggs, which are dark to begin with and thus more difficult to candle.You can clearly see the air sack at the bottom of the egg.

Here’s an egg in which you can see some veins and perhaps a developing eye, right on the line between shadow and light.

Here’s an egg, unfortunately one of the two remaining olive egger (Oregano’s) eggs, that I think has no development:

Here’s a Black Copper Marans egg that appeared very porous. This porosity is thought to be an indication of a poor egg for hatching.

The clearest picture came from the last egg I candled, a Coronation Sussex under Dahlia. You can definitely see a healthy pattern of veins, and as I watched, I could even see the embryo moving within the shell.

I have to admit that holding this egg in my hand, in the dark, and seeing those veins pulse is a pretty freaking incredible feeling. It’s scary, to hold such perfectly planned beauty alive within that fragile shell.

Out of the 20 remaining eggs, there is only one (the olive egger) that I feel I can conclusively describe as not developing. The rest are big question marks, and I am not yet experienced enough to discard any eggs based on my judgement. I feel better about the clutch under Dahlia, my Black Copper Marans, than the clutch under Oregano, my olive egger. But that’s just a hunch. So they will all stay put in the nest, and we will wait the ten more days to see what becomes of them. As you can already tell, a lot can happen in the next ten days. And so I remind myself, and you, dear reader: “Don’t count your chickens until they hatch.”

June 21st, 2013 §

It’s the longest, lightest day of the year, and a lovely one at that. I spent the afternoon processing strawberries picked yesterday in Nelson County.

Summer fruits are the best, but you know what’s even better? Strawberry shortcake, baking in the oven right now. And the chickens definitely enjoyed the strawberry trimmings!

I’ve got a couple of growlers of Devil’s Backbone in the fridge and new friends on the way with fried chicken. We’re doing this Solstice up right with a good old-fashioned porch party on this beautiful evening.

Whatever you’re up to today, I hope you get a chance to celebrate the Solstice. And lest the sun hog all the astronomical attention, don’t forget to check out this weekend’s Supermoon!

February 5th, 2013 §

One upside of attending to my Lavender Orpington’s wound on Sunday was that I discovered she had lice. And when I snagged Oregano, my barred olive egger, for inspection I saw that she too had a few creepy crawlies. It was time for an intervention.

With a healthy flock, regular dust bathing will keep most parasites at bay. But in winter, with its frozen or muddy ground, the birds aren’t able to dust bathe as much as in the warmer seasons. This gives lice a chance to populate the birds. If unchecked, these blood-sucking parasites will deplete a bird to the point where it dies.

Thankfully my flock was no where near that stage. Yet, after spending a night researching various treatments I decided to go straight for the chemical intervention and not waste my time with more “natural” or “organic” methods. I really wanted to nip this infestation in the bud, particularly as it’s still winter and the birds need all the energy they produce just to keep warm and regrow the feathers they’ve lost. And, in another few weeks (if I can get Iris to go broody again) I’d like to try hatching some eggs, which means all my birds should be as healthy as possible and louse-free to avoid passing the bugs on to more-vulnerable chicks.

So I picked up a can of poultry dust, which is a permethrin-based formulation that you may have used for insects in your vegetable garden. I assembled my tools:

I also suited up in latex gloves and a dust mask. Well, the gloves were a joke because it took just one kick of a captured chicken to shred them. I went through five pairs through this process and still ended up covered in dust. If you’re concerned about skin contact, I’d suggest heavier gloves for this job. And, really, with all the flapping and wind I ended up covered with this dust so if you are truly concerned it may not be the treatment for you to use.

Cora, the Wheaten Ameraucana hen, was the first I caught in the coop. Following the advice of a YouTube video, I flipped her on her back. This seemed to calm her enough that I could powder under her wings, a favorite parasite hiding spot. I held her upside down to work the powder in to the feathers under her vent, which is where I saw the lice in all my birds.

Lilac was up next.

And so on through the flock. I left the injured Lavender until last so I could inspect her wound. It was open and bleeding, which I prefer to closed and infected, and seemed a tiny bit smaller than on Sunday.

I packed it full of neosporin before dusting her.

Now that’s a Lavender Orpington!

With the flock dusted, I did some housekeeping in the coop. I sprinkled food-grade diatomaceous earth in the nest boxes, in the chicken food, and filled a litter box with the stuff for dust-bathing in the coop. The diatomaceous earth, which is actually decomposed hard-shelled algae, acts in a mechanical manner (as opposed to chemical) on insects by slicing open their soft bodies, killing them.

And with that the delousing procedure was complete. Now I get to look forward to ten days from now, when I repeat the powdering to kill any nits that will have hatched since today. Fun times!

February 3rd, 2013 §

If you are sickened by chicken wound pictures or first aid, this would be the post to skip.

This morning as I let the chickens out to range, I grabbed my smaller Lavender Orpington hen as she came out of the coop. I’d knew she had a wound for at least a couple of months, and I’d been watching it. I suspect that without feathers to protect her back, courtesy of my feather-picking hen, my rooster had sliced the Lavender’s back with his claws when he mounted her. What had been a small black hole was now a wound the size of a golf ball, hidden behind her wing.

Today, for the first time, the wound smelled bad. And when I flipped the hen over, I found a messy bottom and some sort of infestation in the fluffy feathers under her vent.

With her missing back feathers, purple Blu-Kote stains, a huge necrotic wound, and some sort of insect problem, this chick was a mess.

The evidence for culling her mounted as I considered her performance. This hen wasn’t a great layer, always depositing smallish eggs on the coop floor where they usually grew dirty enough that I fed them right to my dog. I’d made up my mind I didn’t want to continue to keep Lavender Orpingtons because I found their super-fluffy butt feathers to be always collecting poop and debris. And if she hadn’t managed to heal her back wound, did I really want to continue her genetics in my barnyard mix?

But what started as a snowy day had turned sunny, so I returned the hen to the flock for one last day of free ranging before I did the deed. And in the ensuing hours I thought about how I would. I had settled on beheading by branch lopper when I went out around noon to give the chickens the goodies in the compost bucket. When they saw me they all came running, including Dead Hen Walking. When I shook the compost around the garden, she was just as active as the other birds. I stood watching her for a long time, and when my feet finally grew too cold to stay outside any longer I had decided to put some effort into healing this bird.

With eight laying hens, two of which aren’t very stellar in their production rate, this Lavender’s dirty eggs represented a big percentage of my flock’s output. And I’d recently decided to free range my birds as much as possible, and thus some of her value lies in her insect control ability and manure production. Plus, I am fully expecting some predator loss during ranging. After considering the time and expense and food and care that I’ve put in to this bird since I got her in June, to get her grown and laying, it seemed foolish to cull her if she was still up and about and acting fine—even though the last thing I wanted to do was nurse another chicken.

But nurse her I did. I caught her and brought her into the surgery, my laundry room sink. I filled her back wound with peroxide while I soaked her dirty bum feathers in warm water. I scrubbed her clean with dog shampoo and then used needle-nosed pliers to remove the feathers that were caked with the eggs sacs of what I later found out were chicken lice. Underneath her plucked feathers she looked very much like the start of a supermarket dinner. When her back wound had softened I scrubbed it out with a disinfected toothbrush, loosening the blackened tissue and rinsing it down the drain. Then I alternated rinsing peroxide and providone iodine in the wound.

And through what must have been a horribly painful event, this blessed little hen put up nary a struggle. I’ve found my Lavender Orpingtons to be the sweetest, slowest, and most docile of all the breeds I keep, and her demeanor definitely showed through this treatment. She even seemed to enjoy the warm water soak.

When I had her cleaned up as best as I could, I got the hair dryer and blew her dry. I didn’t want her to get chilled when I returned her to the coop, and she bore this treatment with good graces that none of my other pets possess.

I worked on her until she began to smell of rotisserie, and then squirted even more iodine into her wound. Then I wrapped her in a towel and took her outside.

There she got a good spray of Blu-Kote to discourage her flock mates from pecking her bleeding, reddened skin. Then I released her into the coop. And within one second my rooster jumped on her back to mate. That kind of pissed me off, so I knocked him away and left them to their lives.

I don’t know if I will be able to get this hen’s back wound to heal, but I will keep trying. If Cora taught me anything it’s that chickens are incredibly resilient. Tomorrow I am going to get some diatomaceous earth and create a dusting box for the birds. Apparently chicken lice populations bloom in winter when the birds can’t dust bathe because of frozen or muddy ground. So I will start as conservatively as possible to treat the lice, keep an eye on the Lavender hen, continue allowing the birds out to free range as much as possible, and dream of spring.

November 26th, 2012 §

On November 8, Cora laid her first perfect blue egg. This was a discovery of pure joy as Cora—my only Wheaten Ameraucana pullet— survived a vicious attack in her young life and walked so close to death for several months as her scalped head healed.

The Black Copper Marans have also started laying (darkest brown eggs above), as well as the Lavender Orpingtons (light-toned eggs above). Lilac and Iris still seem to be keeping up in their second year of laying. The light on a timer set to turn on at 5:00 a.m. seems to be doing the trick to foil the low-daylight hour laying slowdown. My record has been seven eggs in one day, which of a flock of eight hens is a pretty good return. I am not sure that my “barred olive egger” Oregano has laid yet—if she has, she’s not an olive egger!

One of the best parts of my day is picking up the eggs. It’s this pleasure that exists to offset the pain of discovering and nursing bleeding mostly dead birds, managing flock integration, mucking out the coop, and all the other rough aspects of being mother hen.

Recovered, and now productive, Cora, with only a slightly mussed feather pattern about her beautiful head to belie her hard young life.

October 8th, 2012 §

One of my lavender orpington pullets came online today and laid her first egg. That extra light in the morning must be working. Here’s her egg on the right, next to Iris’s daily contribution. Not bad for a pullet egg—and she even managed to get it in the nest box! I am excited to see the other young hens start to contribute to the daily egg count.

In other news, I ran out to the garage this evening—in my slippers—to retrieve something from the car. On my way out I looked down and saw this:

Looks like I’d smashed this black widow on the floor! That’s pretty close for comfort…weird too as last Friday night I dreamed I was bitten by something on my foot, I saw two marks and dream-assumed it was a snake bite but maybe it was a spider warning!

If you had any doubt, I flipped this lady over to show her identifying red hourglass. She was pretty good-sized!

Tonight’s our first taste of the coming winter. It’s in the low 40s and grey and rainy. My house is about 63 degrees without the central heat yet on and I am eying the woodstove with longing. Too many other things to do tonight to get involved with the first fire of the season, so that will have to wait and in the meantime I am in triple layers of wool and sheepskin. Plus, it’s supposed to return to the 70s later this week!

October 4th, 2012 §

In the last couple of weeks Cora, the maimed hen, has taken a shining to me. I first noticed when I was servicing the food and water in the coop and she ran across the floor and jumped on the roost to get closer to me. Since then she would try to follow me everywhere in the coop, even out the door, and when she was outside in the run she’d throw herself at the fence if I was on the other side.

Tonight I had taken care of the birds and was standing in the coop watching them. It was dusk and they were quiet and starting to roost for the night. Then all of a sudden Cora flew off the top perch of the roost straight for my arm, which is where I’ve let her perch in the past. She misjudged her landing by a few inches and scrabbled at me with her claws. So now my left arm looks like I’ve been in a bear fight, but I have no doubt of my chicken’s affection. I guess a scratched and smarting arm is what I get for saving her life!

September 27th, 2012 §

I didn’t think many people would want to start their day watching eight live chickens be “harvested” and processed, but the conference room for the 10:00 a.m. “Pluck A Lotta Chickens” live demonstration was standing room only way before the presentation began. There must have been 500 or more people there to learn how to slaughter and butcher chickens.

David Schafer, the very easy-on-the-eyes creator of the Featherman line of poultry processing equipment, and Joel Salatin, our previously mentioned hero of the grass farming movement, stood at the front of the room and introduced us to the morning’s teachers: four Cornish crosses and four Freedom Rangers that had been lovingly reared by a nearby farmer, in the green shirt below, and his family. The birds were big and glossy and gorgeous, a far cry from the half-dead creatures I saw yesterday on the road.

After David and Joel took a moment to acknowledge the birds for their lives and their caretaker for his work raising them, David placed the birds one-by-one, head down, in a wheel of metal cones. He gently extended their heads and carefully sliced the artery right under their jawbones. The blood dropped out of the birds in a gush as they calmly blinked a few times, losing blood pressure.

In a minute or so rigor mortis set in and the birds, which were no longer conscious, flapped wildly in their cones. David let the birds continue to bleed out for a few minutes more before putting them in a rotating scalder.

From there he put the birds in a feather plucking machine that bobbled them around until their feathers were rubbed off by rubber fingers. Then Joel took over with the butchering.

First, he pulled the head off the bird, above, a movement that surprised me by its ease. It was a bit shocking to me how easily the head came away from the body, especially after having worked so hard to keep a head attached to one of my own birds. Then Joel cut off the feet and the oil gland above the tail.

He then made a small incision in the front of the bird to access the windpipe and crop, which he loosened by scooping his fingers under it—taking a moment to remind us to fast our birds for a day before slaughter to make this process cleaner. Then he made another incision at the back of the bird around the vent and was able to pull all the viscera out with one hand. A quick tuck of the legs into a slit in the chicken’s skin and it was ready for an ice-water bath. Joel told us that when racing, he could process a chicken in 20 seconds. Wow.

The best part of the demo was how easy it looked. I’d always been a bit intimidated at the thought of butchering a chicken, anticipating a horrible bloody mess and suffering creature, but after watching these teachers—who are the most famous in the business—I think I could do it. Who knows, maybe next year will find me raising a bunch of Freedom Rangers for my freezer!

After this session I wandered over to Christy Hemenway’s talk about keeping bees in top bar hives, which look like a child’s coffin on legs. Christy runs Gold Star Honeybees in Maine and wrote “The Thinking Beekeeper.” I’ve been dancing around the idea of keeping bees for a couple of years, and have even joined the Central Virginia Beekeeping Association. But after a few meetings and a workshop I started to think that the odds are stacked against the beekeeper. Between big predators, such as bears, and tiny marauders, such as the varoa mite, I had grown disheartened even before setting up a hive and decided beekeeping was a fool’s game.

Top bar beekeeping, though, just might change my mind. In a top bar hive, bees build their own wax combs suspended from narrow wooden bars instead of colonizing premade wax foundations, which are often made from beeswax that’s been treated with pesticides to kill varoa mites. Not exactly something you’d want to eat. And when bees build their own combs, they actually build cells of a size that can’t accommodate the varoa mite. It’s a bit more of a production to extract honey from combs built in top bar hives, but the health of the bees in such a system would more than make up for the inconvenience.

After the bee talk I got some lunch. Strangely enough I went for the chicken kabobs…and noticed while in line that my choice of outfit was well-aligned with other festival goers.

Then on to hear Patricia Foreman talk about gardening with chickens. I’d seen Patricia speak the weekend before at the Heritage Harvest Festival, and her talk was pretty similar to what I’d heard there. She advocates putting our chickens to work creating compost. As the cost of feed is increasing, and my flock size grew this summer, I was all ears. The idea I took away from this talk was that I’d like to turn my chickens out into my garden once everything freezes. I hope that they will till up the dirt and in addition to fertilizing eat all the insect eggs that are plaguing my gardening life. I’d also like to figure out how to build a chicken tractor that can detach from my coop and be moved around the yard, instead of building a permanent run.

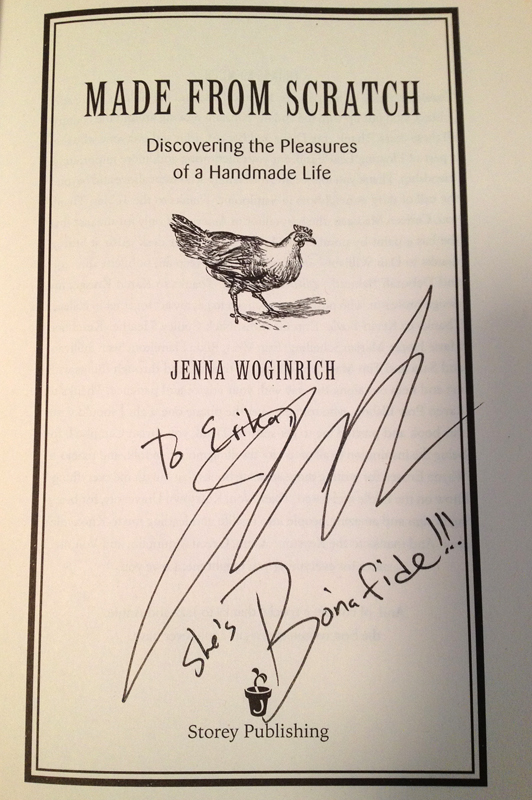

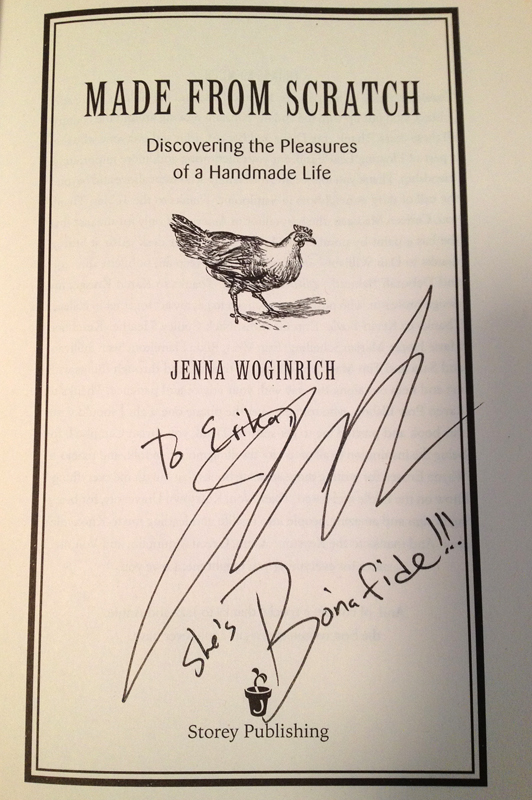

Next up was a talk by Jenna Woginrich, of Cold Antler Farm, about how she makes her living blogging and writing. Jenna is an enthusiastic and natural speaker who kept her audience laughing. As I suspected I would be, I was even more inspired by her in person than I’ve been from years of reading her blog. Jenna boiled her success down to a combination of flexibility and stubbornness—necessary traits, she claims, for the self-employed. I admire Jenna for bucking convention and being one to say no thanks to a society that trains us to, “be scared to do what we want to do.” And we don’t need to have all the answers before we start something new—the important thing is to just begin. As she says, “You can drive to L.A. in the dark. Your headlights will get you there 200 feet at a time.”

I stuck around in the same meeting room for the next talk by Wisconsin farmer Ann Larkin Hansen. I’d heard her speak for a few minutes the day before on woodlot management, but her next presentation was on making hay. I wanted to figure out when was the best time to cut hay for optimum nutritional content, and Ann told us the legumes are the key to when to cut. You should make hay when the legumes have grown as tall as they are going to get and are starting to bud and the grasses are just starting to develop their heads. As crops grow taller, beyond this point, the quantity of your hay increases but its nutritional quality decreases. Leave 2-3″ of stubble in the field when you cut to help prop the hay off the ground, which makes it dry faster. Dry hay is key. Wet hay, if baled, can compost and selfcombust and burn down your barn. Not cool. Ann then got into haying machinery and I slipped out to meet Jenna at her booksigning.

As hoped, I got to talk with her for a few minutes and tell her a bit about my farm. I bought all her books and she signed them for me before she had to run out to give her keynote, which highlighted the importance of community to any farming endeavor. Certainly true, especially for single farmers such as Jenna and myself!

And then day two of the fair came to a close and I retired to dinner and a wonderful hotel sleep. I always sleep well in hotels—I think the secret lies in blackout curtains!

Stay tuned for day three, in which we learn about heritage goats and “make friends with our kombucha!”