July 18th, 2014 §

Well, there are lots of cool chickens in the world, but this one is pretty neat. This week my mom and I were driving around the Shenandoah Valley and found a lavender farm. There were a bunch of beautiful chickens walking around, but this one was exceptional.

She was a tiny little girl, about the size of a 14-week-old standard chicken, and her feathers were the most remarkable opalescent porcelain blue, buff, and pearly white. She had crazy fancy feathered legs. She made fantastic little noises and was so charming I wanted to stick her in my pocket and smuggle her home.

I figured out that she’s a Belgian d’Uccle. I’d love to have a few of this bantam breed some day, even though I am not sure how they’d do housed with the big guys. So many chickens, so few resources to collect them all!

Do any of you have insight about keeping d’Uccles?

June 8th, 2014 §

The two little pullets that hatched in March are twelve weeks old today. I know it’s poor judgement on my part, especially given a day-time fox sighting at the back of the property last week, but I have grown rather fond of them. They are incredibly cute, and are more tame than any of the other chickens I have raised. They are still small enough that I can easily hold both in one hand. They think nothing of half-flying, half-running all the way across the unknown lawn toward me when they feel threatened. Adorable.

A couple of weeks ago, when I finally got their injured broody mother reintegrated into the main flock, I moved the chicks from their broody coop in the garage into a big dog crate in the main coop, where they have their own food and water. They are getting used to being with the main flock while still being protected from attacks. I have also started letting them free range a little, turning them loose in the front garden while I am outside. They’ve met the larger birds during their rambles, and of course were chased and pecked back (but not injured) into hiding places in the bushes.

They discovered dust bathing the other day. The hilarious thing was that despite having access to a whole garden of soft soil, they chose to bathe right on top of one another, kicking each other in the heads as they burrowed into this new experience.

It’s neat to watch the chicks explore their world. They are in many ways like kids and baby animals everywhere—a mixture of boldness and trepidation.

Against my better judgement of growing too attached to animals that could at any moment meet their ends in a number of horrible ways, I have named them Buttercup and Clover.

May 12th, 2014 §

Last week most of my car trips included a chirping cardboard box riding shotgun. I delivered the chicks, which hatched in March, to their new owners. The little black pullet went to an acquaintance, a Wheaten Ameraucana pullet found a new and loving home with one of my Master Gardener friends, and the four Wheaten Ameraucana cockerels sold on CraigsList within an hour. Isn’t he handsome?

I kept two pullets. One is a pure Wheaten Ameraucana (in front below) and the other is a mystery hatched from a green egg out of a black mother! I love chickens at this age—about ten weeks—because they are sweet and curious, fully feathered but still small enough to pick up with one hand. They’re like little mini chicken pocket pets.

During the day I take the pullets out of their broody coop in the garage and put them in Tucker’s old puppy crate on the grass, and they eat their fill of clover, chickweed, whatever unfortunate bug comes along, and any grubs I unearth while digging in the garden. Last night they got to try pear for the first time.

I am a bit sad that chick season is drawing to a close. If I could, I’d raise chickens all year long. I don’t think I will ever get tired of watching eggs turn into bright-eyed, beautiful birds.

Speaking of which, Mr. and Mrs. Bluebird are busy with their brood of four in the bluebird box. It’s wonderful to be back in bluebird season.

And finally, on a less joyful note, the feisty broody hen that hatched this latest batch of chicks wasn’t feisty enough when I returned her to the main flock. Despite holding her own for two days, on the eve of her third day back I found her with a quarter-size hole torn in the back of her skull. In her pain and panic to get away from her attackers she actually jumped into my arms from the nesting box. It’s the exact same wound Oregano sustained under similar circumstances, though this hen’s is worse.

She’s been getting daily Bactine spray and Neosporin plus Blue-Kote spray (which dyes her wound purple). I wish that I would have stitched her wound when I found it. She keeps knocking it open and it’s taking a very long time to heal, having to close from the outside in across basically her entire skull. In fact it’s larger now than it is in this photo, which I took a couple of weeks ago.

She doesn’t act hurt and has returned to laying eggs. As long as her wound doesn’t get infected I will just keep what I am doing and let it heal itself. My experience with Cora taught me that chickens can recover from the most dramatic wounds. This little hen is protected within another dog crate within the main coop, and will be until she heals and can successfully reintegrate with the flock.

This is what she gets for successfully raising the offspring of her sister flock mates. The injustice!

April 26th, 2014 §

The creation of the chick waterer went so well that I wasted no time in making a few more for the main coop. These would be permanent containers, so I used clear silicone to install the nipple waterers into a couple of recycled containers. Yes, I buy epsom salts in 10 pound tubs, about fifty pounds at a go. Don’t laugh. Farming really beats up the body!

These are actually pretty great containers because 1. they were free, 2. they’re opaque, which helps prevent algae growth, 3. they’re sturdy—if they held ten pounds of epsom salt they’d have no trouble holding ten pounds of water, and 4. they had well-positioned handles to make hanging easy.

The idea was to get rid of the situation below—hanging waterers that were the bane of my chicken-keeping life. The water got so dirty, downright filthy in the heat of summer, and when the chickens drank it down low enough the whole thing tipped, spilling the water out into the bedding and wetting the wooden floor of the coop enough to cause it to rot. The wet bedding is bad for birds, makes habitat for disgusting flies, and stinks. Plus, the one-gallon waterer needed to be filled twice a day in the heat of summer, and required frequent checking to make sure it hadn’t spilled.

With my new waterers assembled, it was time for some framing in the coop. I assembled a few bucks worth of supplies and fired up the drill.

First I put up some blocking, using a couple of scrap 2×4 pieces.

Then I cut a piece of scrap wood to length and screwed it in place on top of the blocking.

Finally I installed heavy-duty cup hooks to fit the width of the container handles.

And voila! A new chicken watering system!

I taught the chickens how to use the new waterers with the cranberry trick I used in the broody coop, and after a few weeks of use I am still happy with this system. The bedding remains dry, there’s enough water in the containers to avoid filing them every day, and it stays clean and fresh. Down the line I could even add more containers if I wanted. In all this is an incredible upgrade that solved the biggest, messiest problem of chicken-keeping, and I am happy with how it turned out. I only wish these new horizontal nipple waterers would have been available four years ago when I started keeping chickens!

April 25th, 2014 §

I set the new chicken water in the broody coop, using a block of wood to elevate it to the level of the chicks’ heads. I chained it to the coop wall, and that, combined with the weight of the water, was enough to keep the container upright even when bumped by the birds.

The chicks were wary of the new contraption at first, and reluctant to approach. So I took some dried cranberries and stuck them on the ends of the watering nipples. Once the mother hen figured out where she could get a sweet treat, she hungrily pecked the waterers, and in doing so discovered that her action produced water. And that was all it took. In about five seconds she had shown her chicks how to use the waterer, and they all crowded around to explore the new device. It was another great example of why I like using a broody hen to raise chicks—it’s fascinating to watch her teach the babies exactly what they need to know, and they learn from her instantaneously.

These horizontal watering nipples are not recommended for chicks of less than ten days old. It takes a fair amount of strength for them to manipulate the spring-loaded mechanism with their beaks, so I can see how smaller chicks wouldn’t be able to drink from them.

I had marked the starting water level on the side of the jug, just to make sure that the birds were actually getting water out of it during this transition. And I watched them carefully for the next few days to make sure no one was suffering from dehydration. But training them to use the new waterer couldn’t have been easier, and overall it is a huge improvement from the old, dirty, spilling chick fount.

While I was updating the watering system, I also introduced a new feeder to eliminate the problems I was having with the chicks, and mama hen, scratching out and wasting so much food. I drilled a few sets of holes into this plastic trough feeder and wired it to both the side and bottom of the coop. That holds in securely in place against being tipped over, and it’s easy to pop the top off to refill. The birds are wasting much less food with this design.

The birds have been using the new water and food systems for a couple of weeks now, and all is well. Especially for me, as with these simple and inexpensive upgrades I solved two of the most disgusting and wasteful problems of chicken keeping!

April 2nd, 2014 §

Having a broody hen hatch and raise chicks is far easier, to me, than worrying about fluctuating incubator conditions or heat lamps. However, now that I’ve worked with a broody hen a few times, I realize that using a broody raises some specific issues that are easily addressed with a little bit of construction. I hope that publishing my trial-and-error process will save you time and mess and maybe even the lives of your chicks.

A full-size hen in a small broody coop can be like a bull in a china shop. Certain hens are more gentle than others, but the one I am working with now is a real bruiser. She is just acting out a chicken’s nature, which is to scratch and peck everything in sight. But when everything in sight is a newspaper-lined coop, open food dishes, and a top-heavy chick waterer, not to mention eight delicate little chicks, we have problems. The instant I filled the food bowl with chick feed, the hen would scratch it out to fall through the wire cage floor onto the tray below, wasting pounds of food a day, starving her growing chicks, and sometimes flipping the entire heavy, ceramic feed bowl into their heads. Then she’d continue scratching, ripping up the newspapers that lined the coop’s wire floor, which I used to give the chicks a solid, warm flooring to protect them from drafts. And then she’d knock over the waterer, which was usually filled with food, poop, and wet newspaper, draining the water into the spilled food.

I tried all sorts of tricks—tying the waterer in place, using various dishes and pieces of cardboard under the food bowl, but the whole system was a mess despite cleaning three times a day. Disgusting living conditions aside, the final straw was the fatal implication of a tipped-over waterer. Birds as tiny as these chicks can only go for a couple of hours without water before they’ll die.

A lot of internet research revealed that poultry keepers usually have great success with “nipple waterers,” which are used in commercial poultry production. An evening spent typing “chicken nipple” into various Web sites (what will Google think?!) revealed options such as this, which were supposed to be relatively easy to install on the bottom of a bucket:

However, I had a hard time imagining filling the waterer with the valves installed on its bottom, not being able to set it down. What a pain! I thought there had to be a better solution. After more searching, I discovered the much-less-common “horizontal nipple” and ordered a few from an eBay seller. According to this article in Mother Earth News, this new style of nipple was just introduced a few months ago. Instead of being installed on the bottom of the water container, these go on the side. They are spring-loaded and have a little drip cup underneath to catch the water and help the chickens drink.

My new nipples arrived yesterday and I began to build my improved chicken waterer.

I used a gallon aloe vera juice container because its squared off shape fit more easily in the coop, and I thought I had a better chance of a good seal between the nipple and the container if the container walls weren’t curved. I drilled a couple of 3/8″ holes in the container. I considered installing the nipples with silicone sealant, which would surely eliminate leaks, but I wanted to be able to reuse these nipples on another container. So I wrapped the threads with plumber’s tape in hope that it would improve my odds of a leak-proof seal.

My first attempt yielded one leaky nipple, so I took it out and saw that some bits of container plastic in the drill hole were impeding a tight seal. I cleaned up the edges of the hole, rewrapped the nipple threads, and put it in again. When it seemed like it had a good seal, in that the nipples were very hard to turn as they got further into the container, I filled the container with water and let it sit on the porch all afternoon, watching for leaks. When I saw none, it was time to introduce the birds to their new drinking fountain.

Up next: teaching the chickens to use the new waterer and fixing the food dish problem.

March 23rd, 2014 §

For historical record it’s worth noting that last weekend I said goodbye to Griz, the rooster hatched last summer from a well-traveled egg. Griz had been up on CraigsList for months, for free, after he predictably began challenging his father, Calabrese, in bloody fights for control of the hens. I’d separated Griz on his own in a garage coop and left him to await his fate.

Here he is on the way to his new life. He turned out to have the Cuckoo Marans coloration of his olive egger mother but the green and gold feathers came from Calabrese, his Wheaten Ameraucana father.

It’s a funny thing that he got his name from my brother, who I gave naming honors because Griz’s egg spent time in my brother’s refrigerator before being recalled to Free Union to hatch. My brother chose Grizabella as the name for this chick, which when he turned out to be a cockerel I shortened to Griz. Just the other day I was reading some British magazines and learned that “grizzly” is a term used in that part of the world to describe a chicken of this black and white barred feather patterning—something I’d never heard in America. Weird coincidence, huh?

I am happy to report that Griz has gone on to a new family, who kept his name, and a flock of his own, along with a dozen of my hatching eggs. Part of the Bonafide flock will live on now in Madison, VA.

I got an e-mail from Griz’s new owner the other day:

Griz is doing well. He wasted no time on flowers when he met the ladies and they are all fast friends now. Thanks again.

I have to say I have met the nicest people in all my CriagsList chicken dealings. Maybe keeping chickens is particular to a certain personality type—who knows?—but I have always had positive experiences both buying and rehoming birds this way. It’s great to know a chick I hatched from an egg has found a good new life.

Just-hatched Griz, still damp, July 2013

Griz at one week

March 16th, 2014 §

As expected, the eggs under the broody hen began hatching this morning. I was outside doing chores and cleaning up the garage for a long time and heard nothing. I finally peeked under the hen and all these teetering yellow fluffballs started peeping. My heart almost burst from a combination of gratitude, excitement, and awe.

I can’t really explain this emotion I get from hatching chicks, but it’s addictive and drug-like and makes me feel better than few other things. I suspect it stems from bearing witness to the divine, to seeing something so commonplace and taken-for-granted as a chicken egg turn, in just twenty days, into a walking, chirping, perfectly formed and bright-eyed living being.

I don’t consider myself particularly religious, and I don’t have children and probably never will. But I imagine that what I feel watching these chicks develop in their eggs and hatch is a microcosm of both experiences. A microcosm of a miracle. So infinitesimal, and so huge.

March 9th, 2014 §

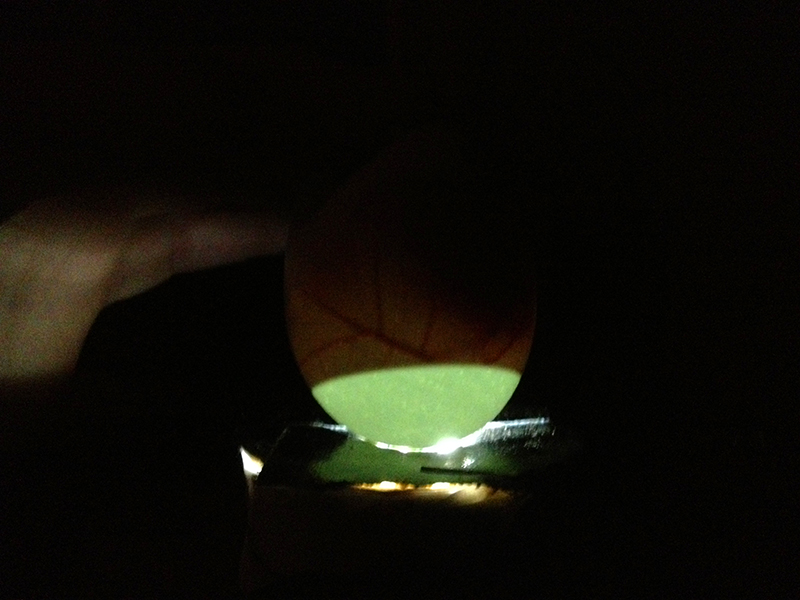

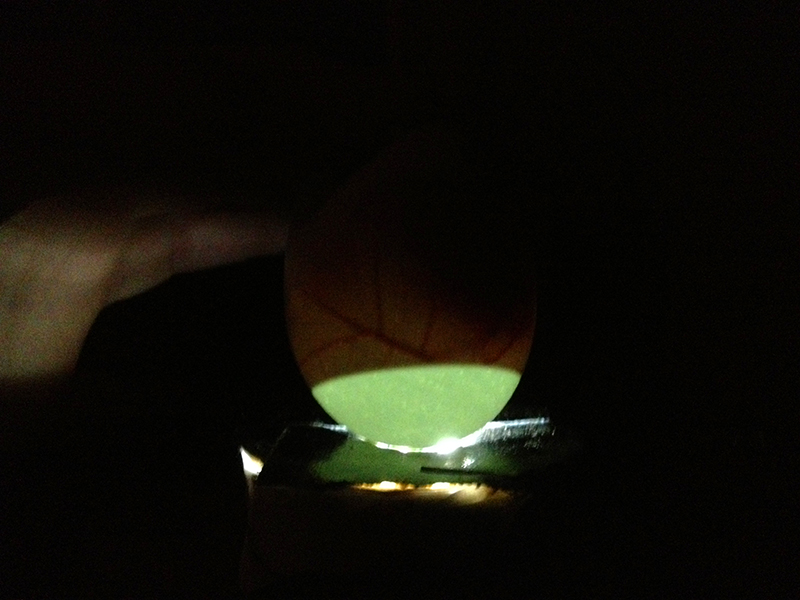

Tonight I snuck a peek inside some of the eggs incubating under the broody hen in the garage. It is much warmer tonight than last Sunday, so I felt comfortable taking a few photos to show you the developing chicks. Again, for a candler I just use a Mag-Light flashlight with the end duct taped but for a dime-sized hole. Here’s what the embryos look like at 14 days:

I didn’t candle all the eggs, but I did enough to determine that I have at least a few little Wheaten Ameraucanas (baby Coras) in development. The pale blue eggs are much easier to see into than brown eggs. If you want to see what the embryos look like inside at this stage, click here.

I didn’t make out too much movement, but that’s typical for this stage of development. Each embryo should soon be flipping around in its shell, pointing its head toward the rapidly-shrinking air cell (the bright, clear blue area in egg) in preparation for breaking through it with their egg tooth at hatching.

There are nine possibly viable eggs left under the hen. Props to the still-unnamed broody hen for keeping all these eggs warm during some seriously cold temperatures last week when it was well below freezing on her nest. If all continues to go well, we might have some St. Patrick’s Day chicks!

March 1st, 2014 §

Last night I drank half a glass of wine and candled the 15 eggs I’d put under a newly broody hen Sunday. What, this isn’t your idea of a rocking Friday night?

Maybe not for most people, but for me candling eggs induces Christmas-morning excitement. There are few things cooler in this world than getting to peek into an intact egg, with nothing more than a flashlight, and see bright red veins, a beating blob of heart and small dark eye. It is a magic trick, a miracle, and all those other things that make me grateful to be along for this wild ride.

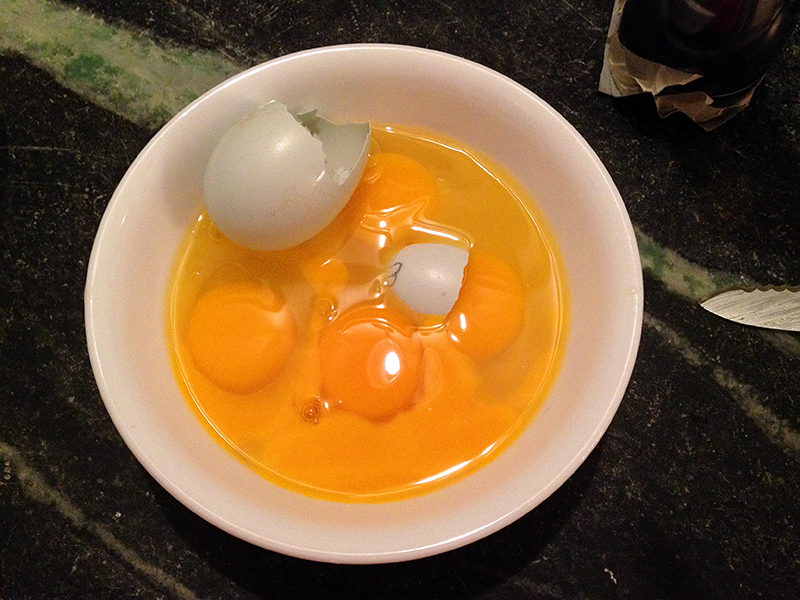

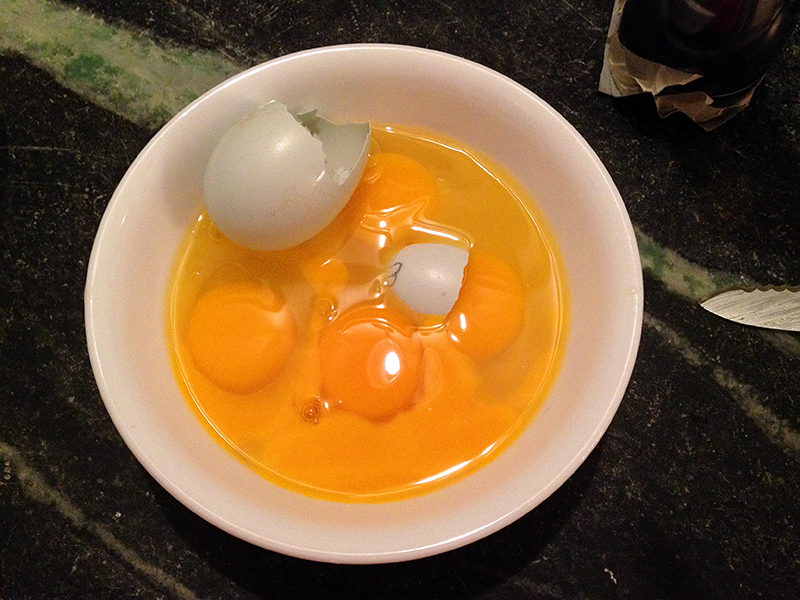

Out of fifteen eggs, eight were definitely on the road to becoming chicks. One egg was a big fat question mark, and I magnanimously returned it to the clutch. I suspected five eggs were infertile, and in the interest of self education I risked destroying embryos to crack the eggs into a white bowl to check. All five were totally clear. My instinct and eye must be getting sharper.

I didn’t take any photos of the developing eggs this time because I wanted them to be out in the cold air as little as possible. In fact, I withdrew them from under their mother two at a time, quickly candled them, and then snuggled them into a pan full of clean towels to hold their heat as much as possible. The whole operation was over in minutes. My pipes may have fallen victim to the polar vortex, but my potential chicks shouldn’t. If you want to see candling photos, they’re here.

I have high hopes for this hen as a broody. She’s one of last summer’s olive egger babies, and there’s a 50% chance she is Dahlia’s daughter. I only mention that because broodiness is a genetic trait. The young broody started plucking her breast feathers out a few weeks ago, and then hunkered down on all her flockmates’ eggs, hissing violently at any chicken that got too close. She’s the only broody out of the four I’ve had that’s actually pecked at me when I reached under her, and I take this feistiness as a good sign. I suppose I should name her as she’s definitely distinguishing herself.

I was on the fence about whether to do chicks again, but finally decided that it’s the best part of chicken keeping and costs me nothing. So I moved the broody to a coop in the garage, where she settled immediately despite being moved during the day, having a raucous rooster (Griz) in the coop next door, and me driving the loud and stinky tractor in and out right after the move. She remained steadfast, I set the eggs, and here we are.

I placed four eggs from my Coronation Sussex, two from last year’s olive egger babies, and nine Wheaten Ameraucana eggs from Cora under the hen. I removed all four of the Coronation eggs tonight, which were all infertile, and one Wheaten Ameraucana egg that was one of the oldest I placed, and had also cycled through the refrigerator as I waffled. I find it telling that my Coronation Sussex hen is the only bird that still has luxuriant feathers on her back and all her eggs were infertile. The hens that laid the fertile eggs are all looking a bit sparse back there because of Calabrese’s attentions. Another lesson learned—keep an eye out for “favorite” hens when scouting future mothers.

I just read back through last summer’s pained posts on hatching eggs, and I have to say that after that experience and this, I will never again let a hen set eggs in the middle of the summer. I realize now that the heat was really detrimental, leading to spoiled eggs that burst and contaminated the nest, and to chicks that were born prematurely and deformed. Incubating in the winter is the way to go. Live and learn.

But then again, we’re only five days into the 21-day incubation period, so let’s not count our chicks before they hatch, right?