September 29th, 2012 §

I got up this morning and, all inspired by the things I learned from Patricia Foreman at the Mother Earth News Fair, decided to turn my chickens loose in my garden. There’s not too much in it now other than flowers and some last-ditch attempts at peas, beans and greens, and I figured that if the chickens took a shining to any of those it’d be no big loss. What I’m really after is pest control.

I caught each bird in the coop and plopped them in the garden, which when closed up in a fairly predator-proof arrangement. I wasn’t too worried about hawks as the dahlias and zinnias were tall and thick enough to provide good cover. Plus, I have a farm dog who took it upon himself to add “vigilantly defends against threats from the sky” to his long list of qualifications.

I checked on the birds throughout the day while I did one of my least-favorite farm chores, mulching around my trees. I wanted to make sure Lilac, who until now had been confined in a dog crate in the coop because she showed murderous tendencies toward Cora, was playing nicely. Everyone was fine all day.

Around five tonight I realized I’d better figure out how to get the birds back in their coop. Now, seven of my nine birds had never ventured further than their little redneck chicken run, and I couldn’t expect to just open the garden door and have them know how to find home. And chasing—and most likely losing—birds that had no ability to figure out how to get to bed before dark induced cringe-worth flashbacks to all the drama suffered with my guineas. I needed another plan.

So I did what any scrappy homesteader would do and looked around for something to repurpose for my needs. I found what I was looking for in a roll of netting that’s usually used to protect bushes from browsing deer. It’s much finer, and therefore easier to handle, than the heavy-duty plastic deer fencing I used around the garden and to make the chicken run. Plus, in addition to an almost new roll, I even had some already used netting balled up in a corner of the garage. I’d stuffed it there after I’d found it in the wellhouse, where it served as a death trap to what was by now a well-dessicated black snake. It’s been long enough that my memory of cutting that rotten snake out of the netting has faded, so I grabbed that piece as well.

A few clothespins later and I’d fashioned a corridor from the garden door into the chicken run. I opened the netting that serves as my garden door and within a second Cora and Calabrese strutted home.

The rest of the birds took a bit of convincing, with Iris and Lilac, who are used to freeranging (and begging for scratch feed) bringing up the rear.

But they too joined the flock in the run, and from there they jumped back in their house to gorge on chicken feed like they hadn’t just spent eight hours enjoying all the wild delicacies of a late-summer garden.

I’ve left left Lilac loose with the flock instead of returning her to her punitive crate. I hope that she decides to be a get-along gal, or she may need to find herself another home. It will be another nerve-wracking morning when I open the coop tomorrow, unsure of what I may find. Let’s hope it’s nine nonbleeding chickens.

In other chicken news, I put a timer on the coop light this morning to artificially extend the hens’ day, thus inducing them to continue to lay through the winter. When the length of daylight slips below about fourteen hours, most hens will stop laying. Last year I didn’t use a light, and Lilac and Iris took a break from laying during the darkest part of the year.

The jury is out on whether it’s “good” or “bad” to have hens lay throughout the winter, with some camps claiming that the hens need the winter to rest even though the original chickens lived near the equator, where daylight hours don’t expand and contract with the seasons they way they do in Virginia. Several variables factored in to my decision, the first being that last winter when my hens weren’t laying I was buying eggs from Joel Salatin’s operation, Polyface Farm. If he was doing something to keep his hens laying in winter, why wasn’t I? Somebody’s hen, somewhere, will have to work through the winter so it might as well be mine. Second, the cost of feed has risen to more than $15 per 50 lb. bag. With each hen eating about a quarter pound of feed a day (thus my experiment to have the chickens forage for a larger percent of their diet), it doesn’t make economic sense to not be getting something out of the bird. As much as I love my chickens, they are not freeloading pets. And even my house pets, a dog and a cat, work for their food in myriad ways. Finally, I got a late start with chicks this year and have six hens—two lavender orpingtons, two black copper marans, a barred olive egger, and a wheaten ameraucana, who have yet to begin laying. I don’t really want to wait until next spring to see the rainbow of eggs they’re expected to produce, so I hope that extra light in the winter will get them in to production before next spring. That light’s coming on in the coop starting at 5:00 a.m. tomorrow, so we’ll see what happens!

September 27th, 2012 §

I didn’t think many people would want to start their day watching eight live chickens be “harvested” and processed, but the conference room for the 10:00 a.m. “Pluck A Lotta Chickens” live demonstration was standing room only way before the presentation began. There must have been 500 or more people there to learn how to slaughter and butcher chickens.

David Schafer, the very easy-on-the-eyes creator of the Featherman line of poultry processing equipment, and Joel Salatin, our previously mentioned hero of the grass farming movement, stood at the front of the room and introduced us to the morning’s teachers: four Cornish crosses and four Freedom Rangers that had been lovingly reared by a nearby farmer, in the green shirt below, and his family. The birds were big and glossy and gorgeous, a far cry from the half-dead creatures I saw yesterday on the road.

After David and Joel took a moment to acknowledge the birds for their lives and their caretaker for his work raising them, David placed the birds one-by-one, head down, in a wheel of metal cones. He gently extended their heads and carefully sliced the artery right under their jawbones. The blood dropped out of the birds in a gush as they calmly blinked a few times, losing blood pressure.

In a minute or so rigor mortis set in and the birds, which were no longer conscious, flapped wildly in their cones. David let the birds continue to bleed out for a few minutes more before putting them in a rotating scalder.

From there he put the birds in a feather plucking machine that bobbled them around until their feathers were rubbed off by rubber fingers. Then Joel took over with the butchering.

First, he pulled the head off the bird, above, a movement that surprised me by its ease. It was a bit shocking to me how easily the head came away from the body, especially after having worked so hard to keep a head attached to one of my own birds. Then Joel cut off the feet and the oil gland above the tail.

He then made a small incision in the front of the bird to access the windpipe and crop, which he loosened by scooping his fingers under it—taking a moment to remind us to fast our birds for a day before slaughter to make this process cleaner. Then he made another incision at the back of the bird around the vent and was able to pull all the viscera out with one hand. A quick tuck of the legs into a slit in the chicken’s skin and it was ready for an ice-water bath. Joel told us that when racing, he could process a chicken in 20 seconds. Wow.

The best part of the demo was how easy it looked. I’d always been a bit intimidated at the thought of butchering a chicken, anticipating a horrible bloody mess and suffering creature, but after watching these teachers—who are the most famous in the business—I think I could do it. Who knows, maybe next year will find me raising a bunch of Freedom Rangers for my freezer!

After this session I wandered over to Christy Hemenway’s talk about keeping bees in top bar hives, which look like a child’s coffin on legs. Christy runs Gold Star Honeybees in Maine and wrote “The Thinking Beekeeper.” I’ve been dancing around the idea of keeping bees for a couple of years, and have even joined the Central Virginia Beekeeping Association. But after a few meetings and a workshop I started to think that the odds are stacked against the beekeeper. Between big predators, such as bears, and tiny marauders, such as the varoa mite, I had grown disheartened even before setting up a hive and decided beekeeping was a fool’s game.

Top bar beekeeping, though, just might change my mind. In a top bar hive, bees build their own wax combs suspended from narrow wooden bars instead of colonizing premade wax foundations, which are often made from beeswax that’s been treated with pesticides to kill varoa mites. Not exactly something you’d want to eat. And when bees build their own combs, they actually build cells of a size that can’t accommodate the varoa mite. It’s a bit more of a production to extract honey from combs built in top bar hives, but the health of the bees in such a system would more than make up for the inconvenience.

After the bee talk I got some lunch. Strangely enough I went for the chicken kabobs…and noticed while in line that my choice of outfit was well-aligned with other festival goers.

Then on to hear Patricia Foreman talk about gardening with chickens. I’d seen Patricia speak the weekend before at the Heritage Harvest Festival, and her talk was pretty similar to what I’d heard there. She advocates putting our chickens to work creating compost. As the cost of feed is increasing, and my flock size grew this summer, I was all ears. The idea I took away from this talk was that I’d like to turn my chickens out into my garden once everything freezes. I hope that they will till up the dirt and in addition to fertilizing eat all the insect eggs that are plaguing my gardening life. I’d also like to figure out how to build a chicken tractor that can detach from my coop and be moved around the yard, instead of building a permanent run.

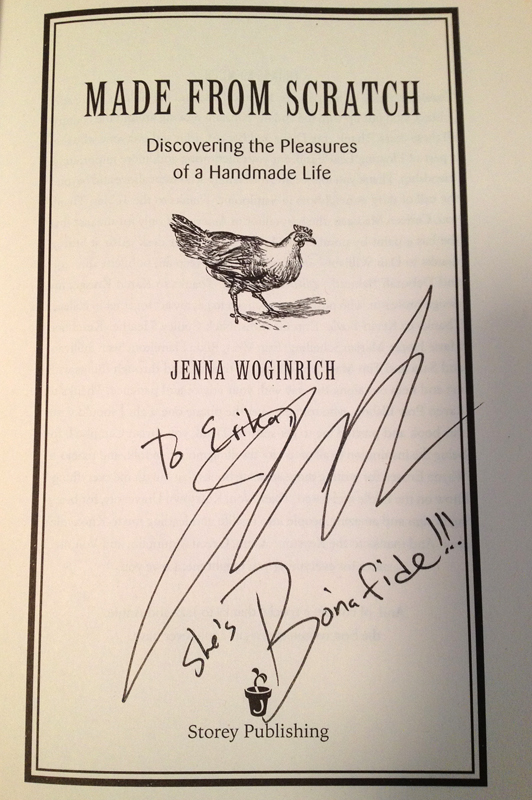

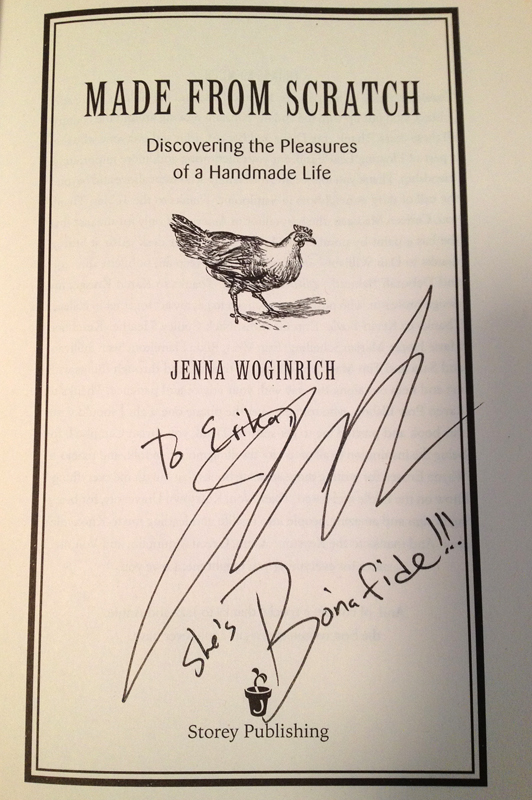

Next up was a talk by Jenna Woginrich, of Cold Antler Farm, about how she makes her living blogging and writing. Jenna is an enthusiastic and natural speaker who kept her audience laughing. As I suspected I would be, I was even more inspired by her in person than I’ve been from years of reading her blog. Jenna boiled her success down to a combination of flexibility and stubbornness—necessary traits, she claims, for the self-employed. I admire Jenna for bucking convention and being one to say no thanks to a society that trains us to, “be scared to do what we want to do.” And we don’t need to have all the answers before we start something new—the important thing is to just begin. As she says, “You can drive to L.A. in the dark. Your headlights will get you there 200 feet at a time.”

I stuck around in the same meeting room for the next talk by Wisconsin farmer Ann Larkin Hansen. I’d heard her speak for a few minutes the day before on woodlot management, but her next presentation was on making hay. I wanted to figure out when was the best time to cut hay for optimum nutritional content, and Ann told us the legumes are the key to when to cut. You should make hay when the legumes have grown as tall as they are going to get and are starting to bud and the grasses are just starting to develop their heads. As crops grow taller, beyond this point, the quantity of your hay increases but its nutritional quality decreases. Leave 2-3″ of stubble in the field when you cut to help prop the hay off the ground, which makes it dry faster. Dry hay is key. Wet hay, if baled, can compost and selfcombust and burn down your barn. Not cool. Ann then got into haying machinery and I slipped out to meet Jenna at her booksigning.

As hoped, I got to talk with her for a few minutes and tell her a bit about my farm. I bought all her books and she signed them for me before she had to run out to give her keynote, which highlighted the importance of community to any farming endeavor. Certainly true, especially for single farmers such as Jenna and myself!

And then day two of the fair came to a close and I retired to dinner and a wonderful hotel sleep. I always sleep well in hotels—I think the secret lies in blackout curtains!

Stay tuned for day three, in which we learn about heritage goats and “make friends with our kombucha!”

September 26th, 2012 §

I left Virginia for the fair last Friday around 8:00 a.m. I had planned my route to Western PA on secondary roads to better enjoy the scenery, and they didn’t disappoint as they wound along rivers and over ridges covered with reddening trees.

I had driven through a snow of chicken feathers for several miles near Broadway, VA, when I overtook a truck on its way to a chicken processing plant.

As I passed the truck I could see that the condition of these birds was appalling: they couldn’t stand and were battered and dirty and missing huge patches of feathers over raw skin. And, sadly, this glimpse I got of them is only the last chapter in lives that we all know aren’t pretty. Seeing those birds made me even more firm in my conviction to not eat commercially produced poultry and to support the farmers who are raising birds in the ways that I would no doubt learn about at the fair.

I cruised up West Virginia valleys and over several mountain ranges before stopping for lunch at Warner’s German Restaurant outside of Cumberland, Maryland. A delicious brat and a mug of beer topped me up to continue on to Seven Springs.

I relied only on my iPhone’s mapping system—Google maps, not the much-maligned IOS6 Apple Maps—and it got me there with only one small operator error. But I was back on track in less than two minutes and along my detour stumbled upon the historic Burkholder covered bridge. In true road trip fashion, best to not plan too much and just roll with it—or through it!

I arrived around two, checked in to my room at the resort, and immediately hit the fair. I listened to the esteemed herbalist Rosemary Gladstar, whose book is my bedtime reading at home, talk about some of her favorite herbs. I was riveted by her. She is a beautiful woman with a shining spirit. If that’s what a lifetime of practicing herbalism gets you, I’ll chew up any number of the weeds growing in my yard and smear them on my face! Rosemary described making a tea and adding a certain flower—calendula, perhaps—to the mix. She said, “I put the gold in there because medicine should be beautiful.” What a wonderful concept, that healing happens with the eyes and that beauty can make and keep us healthy. Certainly that resonates with me and how I live my own life.

After Rosemary’s talk, I headed outside to the vendor tents. One large tent held all sorts of beautiful animals: chickens, geese, cows, pigs, goats, sheep, alpacas and llamas. The intelligent eyes of this llamas really struck me, and his haughty look was a bit unnerving.

I was most enamored of the Underhill Farm booth and their display of skeins of wool from their Leicester Longwool sheep. The owner of the sheep was giving a spinning demonstration and she made the action look both easy and supremely relaxing.

I don’t knit or crochet or know anyone who does, so I had to pass on the gorgeous skeins though they were beautiful enough to display massed in a basket or bowl.

I caught the tail end of Joel Salatin’s keynote about how biological-based systems can produce enough food to feed the world, and he was as charismatic and engaging as the myths make him out to be. Given the audience, I wasn’t surprised to hear almost-evangelically supportive hoots and hollers from the crowd in response to Joel’s statements, but it was curious and wonderful to hear such rock-concert behavior at a talk about the future of our food supply.

Next I headed to a talk on small-scale sustainable farming by David Kline, an Amish farmer.

What stuck out at me was a point David made about the importance of rest as a farmer, which may seem like a foreign concept to many devoted to a lifestyle that requires constant vigilance and recalibration. David’s family slows the grueling pace of farm life on Saturday afternoons, just like his parents and grandparents did, in preparation for the Sabbath. And, he says, one of the built-in checks that forces a healthy stopping point at the end of the day is that, “horses don’t have headlights.”

Then the talks were done for the day and I headed off the resort to find dinner. I stumbled upon the best pumpkin stand I’ve ever seen with a huge variety of beautiful squashes and gourds.

I couldn’t resist filling the back of my car with pumpkins for my parents to thank them for looking after the farm during my absence. Then back to rest, where the reading material provided in the hotel room was right up my alley:

Stay tuned for day two of the fair, which got off to a squawk with a live chicken processing demo!