I had a lightbulb moment today when I realized that there was a way I could use my chickens to control insects in the garden…without sacrificing my plants or produce. I’ve been wanting to let the pest-eating power of my chickens loose in the garden, with hopes that they would attack the harlequin bugs on my kale, and the Mexican bean beetles on my beans. But, of course, when I let the flock in for a trial run they went right to my ripest tomatoes and dug in. They got a few good mouthfuls before I chased them out, and on their way they scratched the heck out of some smaller plants.

I’ve read that some people use bantams (mini chickens) in their gardens to limit the destruction from scratching, and yet other people suggest that Silkie chickens, which have feathered feet, are gentler as they scratch. I’m lacking in the bantam and Silkie departments, but I do have some very mini chickens of my own—the chicks! I knew that with their tiny size they’d be gentler on the plants than the full-grown birds, and being growing babies their appetites just don’t end.

Of course I’d still have to keep the chicks, and their mother, away from the tomatoes. I erected a hasty barricade from a couple of pieces of chicken wire held to the garden posts with zip ties, and then went to fetch my arsenal from the broody coop in the garage.

Dahlia’s relief was palpable when I released her into the fenced-off garden section. After a month and a half of living in small coops, and with half a dozen busy babies, I could tell she was dying for some room to stretch her wings. She scratched in the straw, and then lay down to luxuriate in the cool soil with the hot sun on her wings. Two of her chicks immediately imitated her basking behavior, which almost made me fall over from the cuteness.

Dahlia and her six chicks spent about eight hours in the garden today. Each time I checked on them they were busy scratching and searching for bugs, sticking close to Mom. They spent a long time under the pest-infested kale, which was great to see. The rest of the flock even came around for introductions, which I hope will help ease things when these babies need to join the adults. After only raising chicks in brooders, it’s a real treat to see natural chicken rearing in action.

Around sundown it was time to collect the family to return them to the safety of the garage for night. Now this was a hilarous undertaking. I am glad that the only creature around to witness was my dog, and he didn’t judge. I prowled amongst the vegetation, grabbing chicks. I put the chicks in to a five-gallon bucket to carry them back to the garage, but of course they’re now big enough that they easily fly up to the lip of the bucket and jump out. Each time I’d catch and add a chick, one would fly out and go running for its mother. It was a ridiculous chick chase, soundtracked by Dahlia clucking in concern as each baby was lifted airborne.

Eventually I got all the babies corralled and Dahlia tucked under my arm for our journey home. An ungraceful ending notwithstanding, I think it was a good day out of the chicks, and a big help for the garden.

Today is day 20 for the eggs that are incubating under the broody hens. Last night I discovered another broken rotten egg under Dahlia, the Black Copper Marans, and had to clean that up.

I check the nests this morning, just by listening for peeping, and heard nothing. Then tonight at 6:00 p.m. I went out and saw that Dahlia had thrown one of the remaining Coronation Sussex eggs (two others had already broken during incubation) out of the nest, most likely because she knows it’s not viable.

I heard very faint peeping and took a quick peep under Dahlia’s breast feathers. There I found this dead chick. It appears perfect (look at those toenails, that egg tooth, the cornsilk feathers) except in one vital way. It’s yolk is not entirely absorbed into its belly. Where there should be a clean, dry shell after a hatch this one is a mess of blood and yolk. And its eyes are still sealed shut. It appears that this baby came too early. Not sure why. Could be the hot temperatures, who knows? Perhaps Dahlia even killed it, as some first-time broodies will. I removed it from the nest, Dahlia pecking at it as I dug its sticky body out of the pine shavings.

It’s a sad way to begin the hatch, but beyond my control. By the way I am not posting photos here to gross anyone out. I am posting them because I find a ton of wonderfully educational information on blogs. What “ordinary people” write is often more relevant and specific than the information I find on formal educational sites (for example, the .edu party line is that chicken eggs hatch in 21 days. But because of reading blogs about other hatchers’ experiences, I learned that eggs under broody hens usually hatch on the evening of day 20. And here we are, hatching on the evening of day 20). I hope that by describing and photographing this hatch someone else may benefit from my experience or be able to leave a comment that educates me about how I can do something better in the future.

But back to the coops. There are still signs that more chicks are trying to hatch. Here’s a pipped Black Copper Marans egg.

This chick is inside, faintly peeping, and I could feel and see it move through the hole. I put it quickly back under its mother and checked Oregano, the barred olive egger, very fast.

I could see under her feathers that two eggs had pipped, but I didn’t dig around exploring. Now isn’t the time to fuss anyone up, especially with one already dead hatchling, so I am going to leave them alone and hope that I wake up in the morning to some live babies.

Today marks the halfway point in the incubation of the chicken eggs. It’s been ten days since I placed them under the hens, and my most respected chicken resource states that eggs incubated under broodies usually hatch in twenty days instead of the 21 days for mechanically incubated eggs. We shall see. As it is things aren’t looking awesome in the brood coops, and my confidence in the viability of these hatches is waning.

One of the eggs in Oregano’s coop was broken when I checked earlier in the week, and then yesterday I found the broken shell of a Coronation Sussex egg—the prettiest one of the bunch. Boo.

I don’t know if they are breaking on their own because they are rotten or if she’s cracking (and possibly eating) them. That nest box didn’t smell horribly of rotten egg, so I suspect the egg was fertile when broken. However, I don’t know how many days it would take under the hen for an infertile egg to spoil. So that’s the situation in Oregano’s coop. She’s been getting off the nest, as evidenced by her “deposits” in the cage, and has lost a lot of weight already. Broody hens generally don’t eat much while sitting, and if they do get off the nest their poo has such a strange and horrible smell that it’s enough to gag you just walking into a room with it. Needless to say I remove it as soon as it’s discovered, to keep flies off it and to get it out of my life and into the compost pile.

Over in Dahlia’s coop, I found a major mess in her nest box. One of the olive egger eggs placed under her was broken, and it had made a horrid fermented/cooked mess in the nest. At least five of the ten remaining eggs were coated in dried egg goo. Not good, for several reasons. The incubating egg is a living vessel, and its shell needs to be clean to allow air to pass in to the developing embryo. To seal the pores of the egg could suffocate the embryo.

I was at a loss as to what do. I know the embryos need air, but I also know that to wash an egg is to remove its “bloom” or protective covering that helps keep bacteria out of the egg. In this case, though, I figured washing was probably the lesser of two evil decisions, so I gently scrubbed the dried egg off the dirty eggs.

Oregano had a few dirty eggs too, so I touched those up as well, trying to just wash the dirtiest areas. Then I cleaned out Dahlia’s stinking messy nest, filling it with clean pine shavings. I made notes in my log of which eggs I washed, which may be telling around hatch day.

Of course I started this project before suiting up with gloves, and the stink that was on those eggs was so strong I couldn’t get it off my fingers all night despite multiple scrubbings and soaking in lemon juice. In all, it was a fittingly disgusting ending to an evening that began by killing a black widow in the crawlspace. Ugh.

Tonight it was time to candle the eggs, which means I shine a light through them to see if they are developing into chicks. I made a candler out of a MagLight flashlight (with fresh batteries) topped by a taped-on piece of cardboard to concentrate the beam and cushion the eggs.

Then after dark I headed out to the garage to candle the eggs. All I needed was my candler, my record log and pencil, and a small dish to hold the eggs as I pulled them from the nest. I waited for the garage door lights to go off and began with Oregano’s eggs.

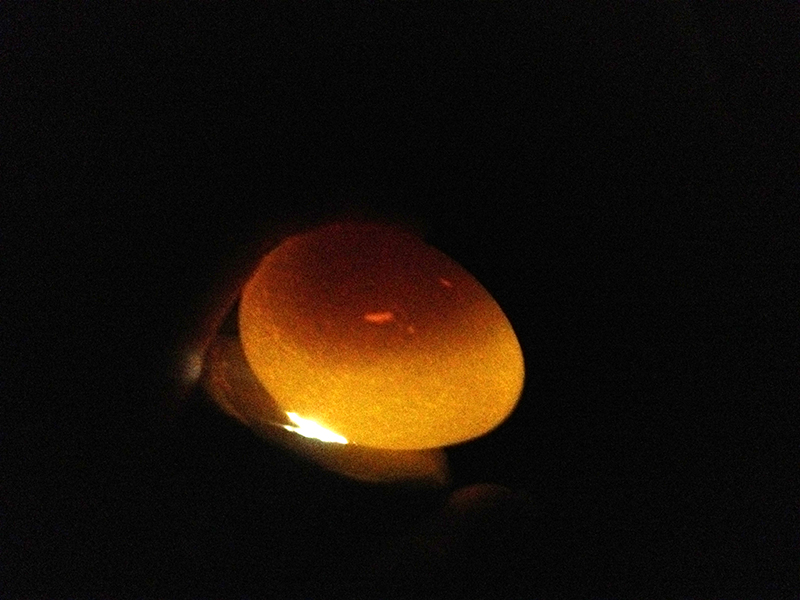

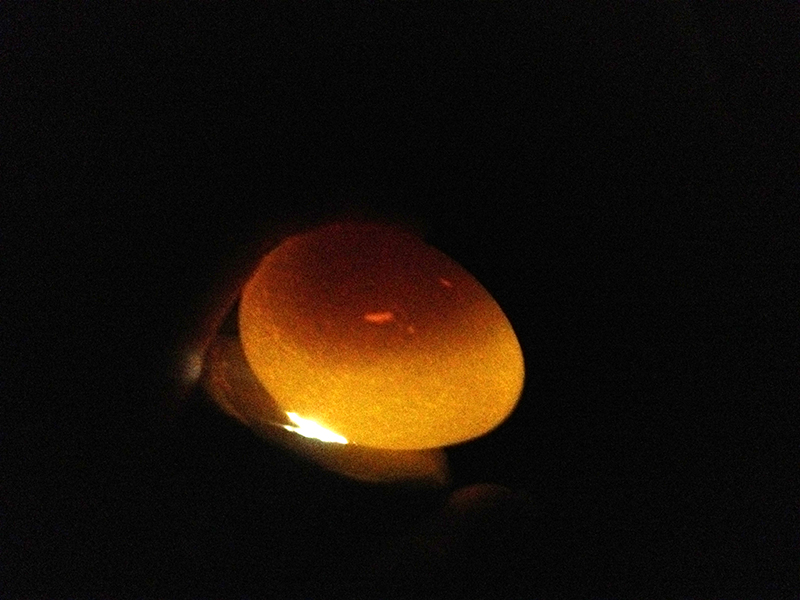

I removed each egg from under Oregano, enduring a peck on the wrist each time, bless her. I held the egg over the end of the candler, turning it until I could see something, or nothing. Most eggs looked like this, below, with some murky shape with no clearly defined blood vessels but perhaps the hint of a developing eye. Perhaps because many of them are Black Copper Marans eggs, which are dark to begin with and thus more difficult to candle.You can clearly see the air sack at the bottom of the egg.

Here’s an egg in which you can see some veins and perhaps a developing eye, right on the line between shadow and light.

Here’s an egg, unfortunately one of the two remaining olive egger (Oregano’s) eggs, that I think has no development:

Here’s a Black Copper Marans egg that appeared very porous. This porosity is thought to be an indication of a poor egg for hatching.

The clearest picture came from the last egg I candled, a Coronation Sussex under Dahlia. You can definitely see a healthy pattern of veins, and as I watched, I could even see the embryo moving within the shell.

I have to admit that holding this egg in my hand, in the dark, and seeing those veins pulse is a pretty freaking incredible feeling. It’s scary, to hold such perfectly planned beauty alive within that fragile shell.

Out of the 20 remaining eggs, there is only one (the olive egger) that I feel I can conclusively describe as not developing. The rest are big question marks, and I am not yet experienced enough to discard any eggs based on my judgement. I feel better about the clutch under Dahlia, my Black Copper Marans, than the clutch under Oregano, my olive egger. But that’s just a hunch. So they will all stay put in the nest, and we will wait the ten more days to see what becomes of them. As you can already tell, a lot can happen in the next ten days. And so I remind myself, and you, dear reader: “Don’t count your chickens until they hatch.”