July 8th, 2013 §

Today is day 20 for the eggs that are incubating under the broody hens. Last night I discovered another broken rotten egg under Dahlia, the Black Copper Marans, and had to clean that up.

I check the nests this morning, just by listening for peeping, and heard nothing. Then tonight at 6:00 p.m. I went out and saw that Dahlia had thrown one of the remaining Coronation Sussex eggs (two others had already broken during incubation) out of the nest, most likely because she knows it’s not viable.

I heard very faint peeping and took a quick peep under Dahlia’s breast feathers. There I found this dead chick. It appears perfect (look at those toenails, that egg tooth, the cornsilk feathers) except in one vital way. It’s yolk is not entirely absorbed into its belly. Where there should be a clean, dry shell after a hatch this one is a mess of blood and yolk. And its eyes are still sealed shut. It appears that this baby came too early. Not sure why. Could be the hot temperatures, who knows? Perhaps Dahlia even killed it, as some first-time broodies will. I removed it from the nest, Dahlia pecking at it as I dug its sticky body out of the pine shavings.

It’s a sad way to begin the hatch, but beyond my control. By the way I am not posting photos here to gross anyone out. I am posting them because I find a ton of wonderfully educational information on blogs. What “ordinary people” write is often more relevant and specific than the information I find on formal educational sites (for example, the .edu party line is that chicken eggs hatch in 21 days. But because of reading blogs about other hatchers’ experiences, I learned that eggs under broody hens usually hatch on the evening of day 20. And here we are, hatching on the evening of day 20). I hope that by describing and photographing this hatch someone else may benefit from my experience or be able to leave a comment that educates me about how I can do something better in the future.

But back to the coops. There are still signs that more chicks are trying to hatch. Here’s a pipped Black Copper Marans egg.

This chick is inside, faintly peeping, and I could feel and see it move through the hole. I put it quickly back under its mother and checked Oregano, the barred olive egger, very fast.

I could see under her feathers that two eggs had pipped, but I didn’t dig around exploring. Now isn’t the time to fuss anyone up, especially with one already dead hatchling, so I am going to leave them alone and hope that I wake up in the morning to some live babies.

June 28th, 2013 §

Today marks the halfway point in the incubation of the chicken eggs. It’s been ten days since I placed them under the hens, and my most respected chicken resource states that eggs incubated under broodies usually hatch in twenty days instead of the 21 days for mechanically incubated eggs. We shall see. As it is things aren’t looking awesome in the brood coops, and my confidence in the viability of these hatches is waning.

One of the eggs in Oregano’s coop was broken when I checked earlier in the week, and then yesterday I found the broken shell of a Coronation Sussex egg—the prettiest one of the bunch. Boo.

I don’t know if they are breaking on their own because they are rotten or if she’s cracking (and possibly eating) them. That nest box didn’t smell horribly of rotten egg, so I suspect the egg was fertile when broken. However, I don’t know how many days it would take under the hen for an infertile egg to spoil. So that’s the situation in Oregano’s coop. She’s been getting off the nest, as evidenced by her “deposits” in the cage, and has lost a lot of weight already. Broody hens generally don’t eat much while sitting, and if they do get off the nest their poo has such a strange and horrible smell that it’s enough to gag you just walking into a room with it. Needless to say I remove it as soon as it’s discovered, to keep flies off it and to get it out of my life and into the compost pile.

Over in Dahlia’s coop, I found a major mess in her nest box. One of the olive egger eggs placed under her was broken, and it had made a horrid fermented/cooked mess in the nest. At least five of the ten remaining eggs were coated in dried egg goo. Not good, for several reasons. The incubating egg is a living vessel, and its shell needs to be clean to allow air to pass in to the developing embryo. To seal the pores of the egg could suffocate the embryo.

I was at a loss as to what do. I know the embryos need air, but I also know that to wash an egg is to remove its “bloom” or protective covering that helps keep bacteria out of the egg. In this case, though, I figured washing was probably the lesser of two evil decisions, so I gently scrubbed the dried egg off the dirty eggs.

Oregano had a few dirty eggs too, so I touched those up as well, trying to just wash the dirtiest areas. Then I cleaned out Dahlia’s stinking messy nest, filling it with clean pine shavings. I made notes in my log of which eggs I washed, which may be telling around hatch day.

Of course I started this project before suiting up with gloves, and the stink that was on those eggs was so strong I couldn’t get it off my fingers all night despite multiple scrubbings and soaking in lemon juice. In all, it was a fittingly disgusting ending to an evening that began by killing a black widow in the crawlspace. Ugh.

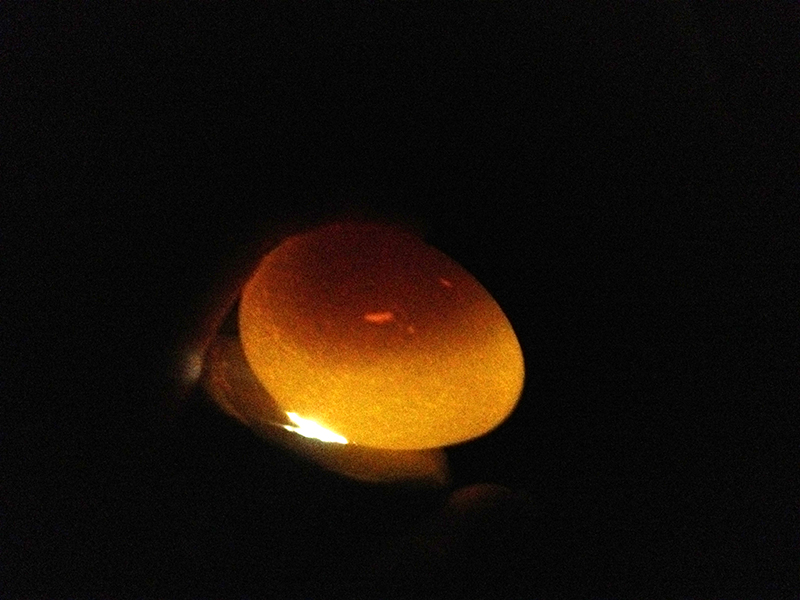

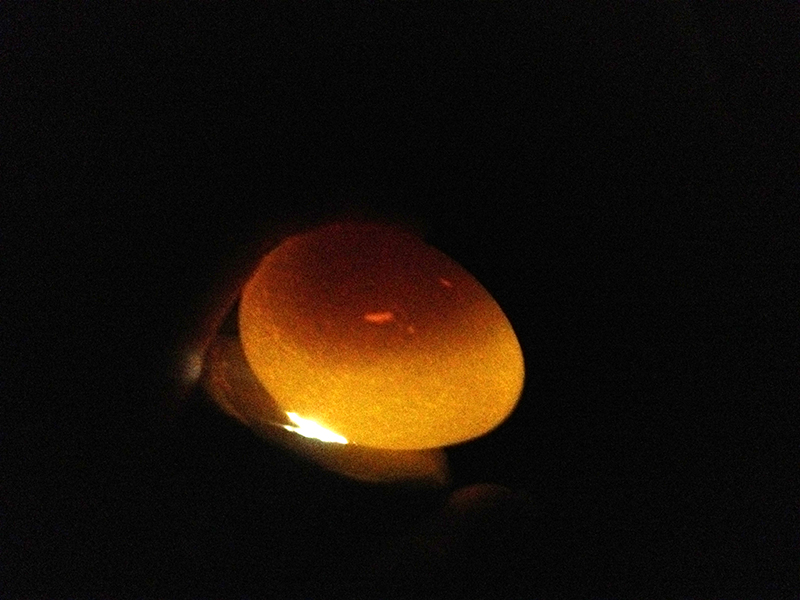

Tonight it was time to candle the eggs, which means I shine a light through them to see if they are developing into chicks. I made a candler out of a MagLight flashlight (with fresh batteries) topped by a taped-on piece of cardboard to concentrate the beam and cushion the eggs.

Then after dark I headed out to the garage to candle the eggs. All I needed was my candler, my record log and pencil, and a small dish to hold the eggs as I pulled them from the nest. I waited for the garage door lights to go off and began with Oregano’s eggs.

I removed each egg from under Oregano, enduring a peck on the wrist each time, bless her. I held the egg over the end of the candler, turning it until I could see something, or nothing. Most eggs looked like this, below, with some murky shape with no clearly defined blood vessels but perhaps the hint of a developing eye. Perhaps because many of them are Black Copper Marans eggs, which are dark to begin with and thus more difficult to candle.You can clearly see the air sack at the bottom of the egg.

Here’s an egg in which you can see some veins and perhaps a developing eye, right on the line between shadow and light.

Here’s an egg, unfortunately one of the two remaining olive egger (Oregano’s) eggs, that I think has no development:

Here’s a Black Copper Marans egg that appeared very porous. This porosity is thought to be an indication of a poor egg for hatching.

The clearest picture came from the last egg I candled, a Coronation Sussex under Dahlia. You can definitely see a healthy pattern of veins, and as I watched, I could even see the embryo moving within the shell.

I have to admit that holding this egg in my hand, in the dark, and seeing those veins pulse is a pretty freaking incredible feeling. It’s scary, to hold such perfectly planned beauty alive within that fragile shell.

Out of the 20 remaining eggs, there is only one (the olive egger) that I feel I can conclusively describe as not developing. The rest are big question marks, and I am not yet experienced enough to discard any eggs based on my judgement. I feel better about the clutch under Dahlia, my Black Copper Marans, than the clutch under Oregano, my olive egger. But that’s just a hunch. So they will all stay put in the nest, and we will wait the ten more days to see what becomes of them. As you can already tell, a lot can happen in the next ten days. And so I remind myself, and you, dear reader: “Don’t count your chickens until they hatch.”

June 17th, 2013 §

Ever since April I’ve been hoping one of my hens would go broody and hatch some chicks. Why? Because baby chicks are some of the things that make life worth living, of course. That and I am seriously curious to see what kind of crosses would result from my Wheaten Ameraucana rooster over Black Copper Marans, Lavender Orpingtons, a Barred Olive Egger, and whatever mix Lilac and Iris are (Black Australorps and Mottled Java, according to their breeder).* Iris and Lilac are in their second year of lay, and it’s good to have younger pullets coming along to take over egg-laying duties. And finally, now that I am free-ranging the birds outside most days, I anticipate that at some point I will have predator loss and don’t want to be caught out with not enough laying hens to keep eggs in the fridge.

A broody hen is a wonderful creature because she manages all the care, feeding, and warming of young chicks. If you have ever raised chicks, you know that it’s a big, messy job to monitor their brooder temperature, clean up after them, keep them safe from drafts and predators, and make sure they get enough to drink and eat. So I told myself that the only way I would raise chicks this year was if a hen did all the work for me!

Last year Iris went unbreakably broody and I ended up giving her a clutch of fertile guinea eggs. She brooded them in a dog crate in the garage and hatched out and raised nine guineas. Here’s one at several weeks old, posing for its CraigsList portrait:

I got to watch the hatch and meet the still-damp keets, and it was one of the neatest days of my life. But this year, Iris has chosen to not do it again. Being trapped in a small cage with nine flighty, frantic, velociraptor-looking guinea keets was probably enough for her to sign off on motherhood forever. Not that I blame her—check out how those ravenous minidinosaurs are eying up their adopted mother’s toes while Iris pleads with her eyes for a Calgon moment.

The most time-tested way to induce broodiness in a hen is to let eggs accumulate in the nest box. When the hen feels a growing clutch beneath her, some hormone switches in her brain that tells her to buckle down and brood. She will remain on the nest, barely eating and drinking, and will often pull feathers out of her breast so that she can keep the eggs tucked right next to her bare skin.

For weeks now I’ve been letting eggs accumulate, rotating out the older ones after a day or two in order to keep some in the fridge. I also placed the infamous glass eggs in the nests to trick the hens in to thinking there were always eggs waiting for a mother. And finally, it started to look like a few of then hens were beginning to feel broody.

Oregano, my beautiful barred olive egger, was the first to show any sort of devotion. After she’d been on the nest about a week, I fixed up a broody coop in the garage and built her a cardboard brood nest. It’s best to have a hen incubate eggs and raise chicks in a quiet, private place away from the bustle of the main coop, where flock mates may see new babies as tasty hors d’oeuvres. I was waiting for nightfall to move her to her new home when one of my Black Copper Marans saw the nest was exposed and jumped up to sit on the eggs.

After dark, when I went to collect Oregano, the Black Copper Marans was still sitting tight on the eggs. One look and I got her message: She wanted a clutch of her own.

Oregano had assumed a broody position in the adjoining nest box. So I grabbed her and moved her and the eggs into the garage coop.

Oregano accepted her new nest and has stayed on it since Friday.

But the Black Copper Marans was still sitting on the glass eggs. And so I fixed up a second broody coop in the garage, built another cardboard next box, and last night moved her into a brood cage next to Oregano. So now I have two broody hens.

I have been saving out eggs for a week or so now, and when I get numbers I am satisfied with I will remove the glass and sacrificial eggs from under the hens and replace them with these fresh eggs. That way all embryos will start to develop at once, and all chicks will hatch at the same time. It’s a bit sad as the eggs are developing under Oregano, but their job really is to just “hold” the hen in a broody mindset until the more valuable eggs are introduced.

I wasn’t really planning on trying to raise two clutches, but at the end of the day it’s not such a bad thing. It means I can hatch more eggs, which is good as there is no way of knowing what the fertility rate is amongst my hens’ eggs. And, if one of the hens begins incubating and gives up, I could move the most valuable eggs to the other hen and have her take over. Thus, I am waiting until the same night to give both hens their eggs, and then we will see what happens! There is still a lot that can go wrong in the 21 days it takes to cook a chick, but I am having fun working with my broodies. If you’d like to know more, allow me to refer you to this excellent article by my favorite author on all things chicken, Harvey Ussery: Working with Broody Hens.

*A quick digression on chicken breeds and egg color: I have the right set-up to produce olive eggers, which, as their name suggests, lay olive colored eggs. To make a nice olive egger, you need a dark brown egg-laying breed (such as Black Copper Marans) mixed with a blue egg laying breed (Wheaten Ameraucana—my rooster). My Black Copper Marans don’t lay very dark eggs and I have no idea what sort of blue egg genetics my rooster carries, so I don’t suspect I will break any records with any pullets I hatch from that combination. But at the very least, I should end up with some sort of green egg, which is plenty exciting to me.

Now here is where it gets interesting. I have three eggs saved out from Oregano, my barred olive egger (the green eggs in the photo above). She does lay a very nice olive-colored egg, when she lays. By crossing her with Calabrese, and his blue egg genes, I may end up with a pullet that lays a really green egg, as opposed to an olive egg. But who knows, really? I have read about chicken genetics until I fell over from confusion and still am not sure what will happen. Mostly because I know nothing about the genetics of the birds I am starting with, other than their supposed breeds and what color eggs the hens lay now. And there’s always the possibility that I will hatch 100% cockerels and then the whole experiment is good for nothing but the freezer. And even if I do hatch pullets, it will be another year until they lay and who knows if I will even be in to chickens then!

September 29th, 2012 §

I got up this morning and, all inspired by the things I learned from Patricia Foreman at the Mother Earth News Fair, decided to turn my chickens loose in my garden. There’s not too much in it now other than flowers and some last-ditch attempts at peas, beans and greens, and I figured that if the chickens took a shining to any of those it’d be no big loss. What I’m really after is pest control.

I caught each bird in the coop and plopped them in the garden, which when closed up in a fairly predator-proof arrangement. I wasn’t too worried about hawks as the dahlias and zinnias were tall and thick enough to provide good cover. Plus, I have a farm dog who took it upon himself to add “vigilantly defends against threats from the sky” to his long list of qualifications.

I checked on the birds throughout the day while I did one of my least-favorite farm chores, mulching around my trees. I wanted to make sure Lilac, who until now had been confined in a dog crate in the coop because she showed murderous tendencies toward Cora, was playing nicely. Everyone was fine all day.

Around five tonight I realized I’d better figure out how to get the birds back in their coop. Now, seven of my nine birds had never ventured further than their little redneck chicken run, and I couldn’t expect to just open the garden door and have them know how to find home. And chasing—and most likely losing—birds that had no ability to figure out how to get to bed before dark induced cringe-worth flashbacks to all the drama suffered with my guineas. I needed another plan.

So I did what any scrappy homesteader would do and looked around for something to repurpose for my needs. I found what I was looking for in a roll of netting that’s usually used to protect bushes from browsing deer. It’s much finer, and therefore easier to handle, than the heavy-duty plastic deer fencing I used around the garden and to make the chicken run. Plus, in addition to an almost new roll, I even had some already used netting balled up in a corner of the garage. I’d stuffed it there after I’d found it in the wellhouse, where it served as a death trap to what was by now a well-dessicated black snake. It’s been long enough that my memory of cutting that rotten snake out of the netting has faded, so I grabbed that piece as well.

A few clothespins later and I’d fashioned a corridor from the garden door into the chicken run. I opened the netting that serves as my garden door and within a second Cora and Calabrese strutted home.

The rest of the birds took a bit of convincing, with Iris and Lilac, who are used to freeranging (and begging for scratch feed) bringing up the rear.

But they too joined the flock in the run, and from there they jumped back in their house to gorge on chicken feed like they hadn’t just spent eight hours enjoying all the wild delicacies of a late-summer garden.

I’ve left left Lilac loose with the flock instead of returning her to her punitive crate. I hope that she decides to be a get-along gal, or she may need to find herself another home. It will be another nerve-wracking morning when I open the coop tomorrow, unsure of what I may find. Let’s hope it’s nine nonbleeding chickens.

In other chicken news, I put a timer on the coop light this morning to artificially extend the hens’ day, thus inducing them to continue to lay through the winter. When the length of daylight slips below about fourteen hours, most hens will stop laying. Last year I didn’t use a light, and Lilac and Iris took a break from laying during the darkest part of the year.

The jury is out on whether it’s “good” or “bad” to have hens lay throughout the winter, with some camps claiming that the hens need the winter to rest even though the original chickens lived near the equator, where daylight hours don’t expand and contract with the seasons they way they do in Virginia. Several variables factored in to my decision, the first being that last winter when my hens weren’t laying I was buying eggs from Joel Salatin’s operation, Polyface Farm. If he was doing something to keep his hens laying in winter, why wasn’t I? Somebody’s hen, somewhere, will have to work through the winter so it might as well be mine. Second, the cost of feed has risen to more than $15 per 50 lb. bag. With each hen eating about a quarter pound of feed a day (thus my experiment to have the chickens forage for a larger percent of their diet), it doesn’t make economic sense to not be getting something out of the bird. As much as I love my chickens, they are not freeloading pets. And even my house pets, a dog and a cat, work for their food in myriad ways. Finally, I got a late start with chicks this year and have six hens—two lavender orpingtons, two black copper marans, a barred olive egger, and a wheaten ameraucana, who have yet to begin laying. I don’t really want to wait until next spring to see the rainbow of eggs they’re expected to produce, so I hope that extra light in the winter will get them in to production before next spring. That light’s coming on in the coop starting at 5:00 a.m. tomorrow, so we’ll see what happens!