My first term as a new horticulture student ended Friday, and I am a strange mixture of relieved it’s over, proud of myself for surviving, and excited to get back to school. The last six months were some of the most challenging I’ve ever lived, beginning with the decision to leave my beautiful farm in Virginia and move to a foreign country where I knew no one, all to try to learn something new at age 35.

And I am happy to say that I have indeed learned a lot, which really came into focus when I received the most recent issue of my favorite magazine, Gardens Illustrated. This British publication is so lovely that I’d actually splashed out on an international subscription when I was still living in the U.S., and it is no understatement to say that the writing, photographs, and knowledge contained within its pages influenced my decision to study horticulture. When I got a U.K. address, one of the first things I did was subscribe to Gardens Illustrated here. My first issue arrived last week, and while paging through it I was amazed to see that after three months of studying horticulture, I am reading a completely new magazine. What’s changed? I’ve learned a new language.

Latin. That language no one speaks but everyone said, while I was growing up, was “just so helpful” for understanding what seemed like everything in the world. As a young student I didn’t study Latin, yet I managed to grow up and become a semi-literate member of society who garnered a fair share of bylines without anyone knowing my secret linguistic deficit.

And then came the first week of horticultural training, and into my hands was thrust a list of 25 plant names. In Latin. That I had to learn to identify from live material and name. It Latin. I swallowed hard. The gig was up.

Before I had time to panic the class was herded outside on a high-speed zoom about the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, trailing our sprightly and quintessentially English head of education as he pointed out each of the plants on the list and where they grew. All while spouting even more Latin.

The class stood beneath a tall tree that had just about dropped all its buttery yellow autumn leaves: Kalopanax septemlobus. Our teacher picked one of the tree’s leaves up off the ground, counted the seven lobes out loud, and tossed it on the ground, scoffing, “It must be broken.”

British humor.

And off we zoomed to the next plant on the list.

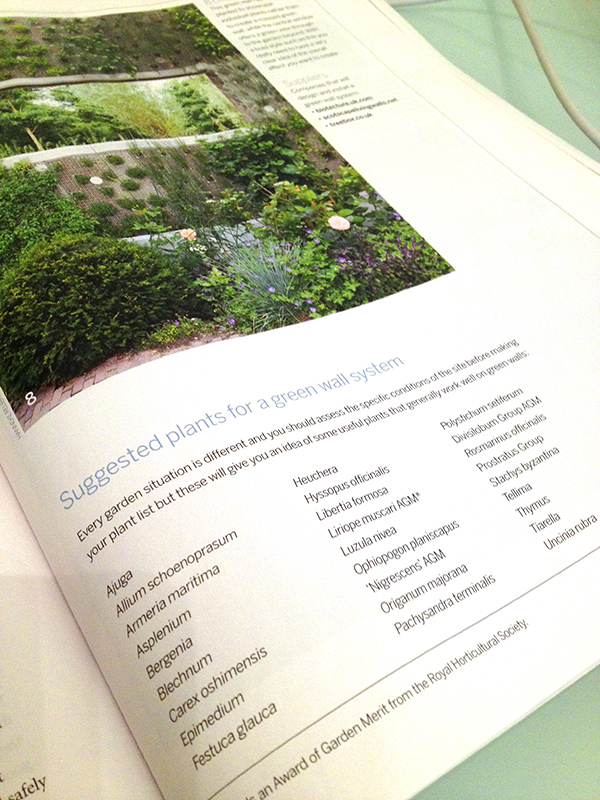

We did this every week with a new list of plants, and one of the things that’s most amazed me about this transition is that I am actually able to learn and remember all these new plant names. In Latin. Which brings me back to reading my magazine, where, because it is a reputable horticultural publication, all plants are referred to by their Latin names. Today, when I read down a list of plants and came across Ophiopogon planiscapus ‘Nigrescens,’ which was just on my last exam Friday, I almost leapt from my chair out of sheer joy of recognition and understanding. Now I know that rather complicated name refers to the relatively prosaic little black mondo grass that edges municipal plantings everywhere. And which isn’t actually, technically, a grass.

For the first time in a life spent loving plants I am learning to call them by their real names. This might not seem like a lot, but one of the major benefits of binomial nomenclature (two name—there I go with more Latin, somebody stop me!—the first being the genus, second species) is that if you know the genus to which a species belongs, you are well on your way toward a basic understanding of the fundamental characteristics of a plant whether you’ve seen it or not. How handy!

Before I began my course, I used to kind of just gloss over those Latin plant names, as one tends to do with things in foreign languages one doesn’t understand. But now, for the first time in my life, I have begun to read and understand this language. And it’s a whole new world.