I didn’t think many people would want to start their day watching eight live chickens be “harvested” and processed, but the conference room for the 10:00 a.m. “Pluck A Lotta Chickens” live demonstration was standing room only way before the presentation began. There must have been 500 or more people there to learn how to slaughter and butcher chickens.

David Schafer, the very easy-on-the-eyes creator of the Featherman line of poultry processing equipment, and Joel Salatin, our previously mentioned hero of the grass farming movement, stood at the front of the room and introduced us to the morning’s teachers: four Cornish crosses and four Freedom Rangers that had been lovingly reared by a nearby farmer, in the green shirt below, and his family. The birds were big and glossy and gorgeous, a far cry from the half-dead creatures I saw yesterday on the road.

After David and Joel took a moment to acknowledge the birds for their lives and their caretaker for his work raising them, David placed the birds one-by-one, head down, in a wheel of metal cones. He gently extended their heads and carefully sliced the artery right under their jawbones. The blood dropped out of the birds in a gush as they calmly blinked a few times, losing blood pressure.

In a minute or so rigor mortis set in and the birds, which were no longer conscious, flapped wildly in their cones. David let the birds continue to bleed out for a few minutes more before putting them in a rotating scalder.

From there he put the birds in a feather plucking machine that bobbled them around until their feathers were rubbed off by rubber fingers. Then Joel took over with the butchering.

First, he pulled the head off the bird, above, a movement that surprised me by its ease. It was a bit shocking to me how easily the head came away from the body, especially after having worked so hard to keep a head attached to one of my own birds. Then Joel cut off the feet and the oil gland above the tail.

He then made a small incision in the front of the bird to access the windpipe and crop, which he loosened by scooping his fingers under it—taking a moment to remind us to fast our birds for a day before slaughter to make this process cleaner. Then he made another incision at the back of the bird around the vent and was able to pull all the viscera out with one hand. A quick tuck of the legs into a slit in the chicken’s skin and it was ready for an ice-water bath. Joel told us that when racing, he could process a chicken in 20 seconds. Wow.

The best part of the demo was how easy it looked. I’d always been a bit intimidated at the thought of butchering a chicken, anticipating a horrible bloody mess and suffering creature, but after watching these teachers—who are the most famous in the business—I think I could do it. Who knows, maybe next year will find me raising a bunch of Freedom Rangers for my freezer!

After this session I wandered over to Christy Hemenway’s talk about keeping bees in top bar hives, which look like a child’s coffin on legs. Christy runs Gold Star Honeybees in Maine and wrote “The Thinking Beekeeper.” I’ve been dancing around the idea of keeping bees for a couple of years, and have even joined the Central Virginia Beekeeping Association. But after a few meetings and a workshop I started to think that the odds are stacked against the beekeeper. Between big predators, such as bears, and tiny marauders, such as the varoa mite, I had grown disheartened even before setting up a hive and decided beekeeping was a fool’s game.

Top bar beekeeping, though, just might change my mind. In a top bar hive, bees build their own wax combs suspended from narrow wooden bars instead of colonizing premade wax foundations, which are often made from beeswax that’s been treated with pesticides to kill varoa mites. Not exactly something you’d want to eat. And when bees build their own combs, they actually build cells of a size that can’t accommodate the varoa mite. It’s a bit more of a production to extract honey from combs built in top bar hives, but the health of the bees in such a system would more than make up for the inconvenience.

After the bee talk I got some lunch. Strangely enough I went for the chicken kabobs…and noticed while in line that my choice of outfit was well-aligned with other festival goers.

Then on to hear Patricia Foreman talk about gardening with chickens. I’d seen Patricia speak the weekend before at the Heritage Harvest Festival, and her talk was pretty similar to what I’d heard there. She advocates putting our chickens to work creating compost. As the cost of feed is increasing, and my flock size grew this summer, I was all ears. The idea I took away from this talk was that I’d like to turn my chickens out into my garden once everything freezes. I hope that they will till up the dirt and in addition to fertilizing eat all the insect eggs that are plaguing my gardening life. I’d also like to figure out how to build a chicken tractor that can detach from my coop and be moved around the yard, instead of building a permanent run.

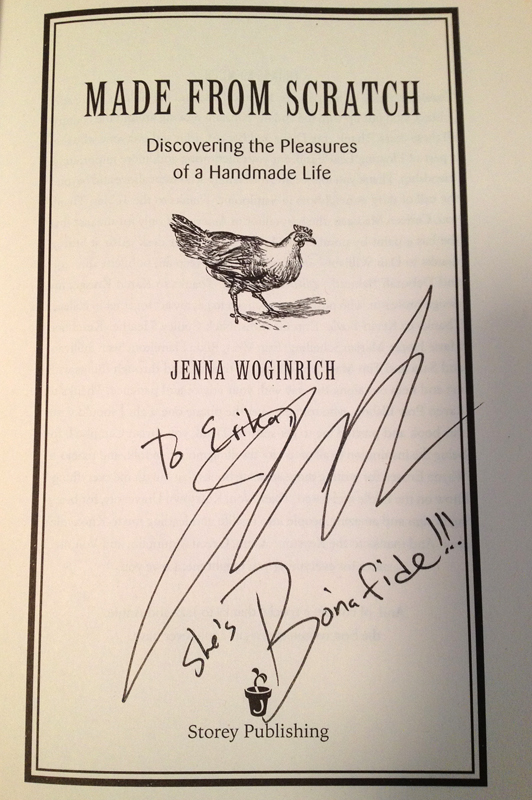

Next up was a talk by Jenna Woginrich, of Cold Antler Farm, about how she makes her living blogging and writing. Jenna is an enthusiastic and natural speaker who kept her audience laughing. As I suspected I would be, I was even more inspired by her in person than I’ve been from years of reading her blog. Jenna boiled her success down to a combination of flexibility and stubbornness—necessary traits, she claims, for the self-employed. I admire Jenna for bucking convention and being one to say no thanks to a society that trains us to, “be scared to do what we want to do.” And we don’t need to have all the answers before we start something new—the important thing is to just begin. As she says, “You can drive to L.A. in the dark. Your headlights will get you there 200 feet at a time.”

I stuck around in the same meeting room for the next talk by Wisconsin farmer Ann Larkin Hansen. I’d heard her speak for a few minutes the day before on woodlot management, but her next presentation was on making hay. I wanted to figure out when was the best time to cut hay for optimum nutritional content, and Ann told us the legumes are the key to when to cut. You should make hay when the legumes have grown as tall as they are going to get and are starting to bud and the grasses are just starting to develop their heads. As crops grow taller, beyond this point, the quantity of your hay increases but its nutritional quality decreases. Leave 2-3″ of stubble in the field when you cut to help prop the hay off the ground, which makes it dry faster. Dry hay is key. Wet hay, if baled, can compost and selfcombust and burn down your barn. Not cool. Ann then got into haying machinery and I slipped out to meet Jenna at her booksigning.

As hoped, I got to talk with her for a few minutes and tell her a bit about my farm. I bought all her books and she signed them for me before she had to run out to give her keynote, which highlighted the importance of community to any farming endeavor. Certainly true, especially for single farmers such as Jenna and myself!

And then day two of the fair came to a close and I retired to dinner and a wonderful hotel sleep. I always sleep well in hotels—I think the secret lies in blackout curtains!

Stay tuned for day three, in which we learn about heritage goats and “make friends with our kombucha!”

[...] got up this morning and, all inspired by the things I learned from Patricia Foreman at the Mother Earth News Fair, decided to turn my chickens loose in my garden. There’s not too much in it now other than [...]